Dying to Be Barbie

Derek & Laura Cabrera

·

1 minute read

Derek & Laura Cabrera

·

1 minute read

This post is an excerpt from Chapter 5 of Flock Not Clock.

Mental models can be simple or wildly complex. They can describe important or unimportant phenomena. We humans create mental models that summarize and are capable of describing, predicting, and altering behavior. In other words, our mental models may lead us to think certain things about the real world and result in actual behaviors in the real world. Even very dangerous behaviors, like the eating disorders anorexia and bulimia. Let’s look at a very familiar example: Barbie.

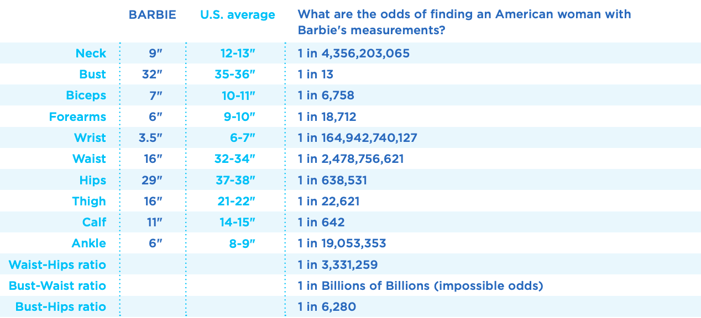

Mattel’s Barbie doll is an icon of female beauty and empowerment in America. Might the mental model of female beauty that Barbie represents have sinister effects? Despite Barbie’s professional achievements (stints as a pediatrician, astronaut, and business executive, among them) and her evolution from the blond archetype to more inclusive representations of multicultural beauty, Barbie’s design remains problematic. If Barbie were a real woman, her physical proportions would make it impossible for her to lift her head or support her body. At human scale, Barbie’s head would be two inches larger and her neck twice as long and six inches thinner than the average American woman's head and neck. Her six-inch ankles and size 3 feet would be unable to support her weight or allow her to balance, forcing her to walk on all fours. Barbie’s 16-inch waist would have only enough room for half a liver and a few inches of intestine.

In a study researching the effect of Barbie on young girls' body dissatisfaction, five- to eight-year-old girls were exposed to images of Barbie (US size 2), a more realistic doll (US size 16), or no dolls (baseline control). They were then asked to complete an assessment of body image.

Figure 5.2: The Barbie mental model is not only improbable, it is in many ways impossible.

Figure 5.2: The Barbie mental model is not only improbable, it is in many ways impossible.

The girls who were exposed to Barbie “reported lower body esteem and greater desire for a thinner body shape than girls in the other exposure conditions.”

Figure 5.3: Which of these mental models reflects reality?

Figure 5.3: Which of these mental models reflects reality?

How might a shift in the mental model of the female form influence children’s self-image, behavior, or perception of others? The makers of the Lammily doll decided to create a doll with a key difference: Her proportions were modeled on the average 19-year-old woman. According to the Lammily website, “We believe that if girls are encouraged to follow their dreams, without focusing on what they should look like, then they will grow up to be confident, strong, and powerful women.”

.png?width=150&height=150&name=CRL%20GOAT%20Logo%20(4).png)