Change Happens One Mental Model At A Time Until You Hit A Committed Minority: CBG as an Organizational Change Tool

Derek & Laura Cabrera

·

9 minute read

Derek & Laura Cabrera

·

9 minute read

This post is an excerpt of Chapter 6 of Flock Not Clock.

We create a culture of vision, mission, capacity, and learning

Leaders often say their most powerful asset is their people. We disagree. People in and of themselves aren’t that powerful, especially if they are bickering, at cross purposes, or ignoring one another. People who share common mental models are powerful. Culture is what happens when people share mental models. Culture isn’t some mysterious thing that only happens if we’re lucky. All groups have culture: culture occurs and evolves naturally. Perhaps most important, culture can be built.

For a mental model to be shared it must be (1) understood the same way by everyone in the group, and (2) believed in and endorsed by the group. To say it another way, when mental models are shared—that is, understood and embraced in the same way—among members of an organization, they constitute organizational culture. Therefore, each mental model—for example, Quality is Job One—must mean the same thing to and resonate with all group members. This is why organizations are best served by concise and unambiguous statements of their vision, mission, and values. (In other words, room for interpretation is destructive!)

So, how shared must a mental model be for it to be considered part of organizational culture? At the individual level, there will always be variation in how deeply understood and ingrained any mental model is. It is unlikely that even the most persuasive leader can perfectly inculcate their vision and mission, let alone myriad other mental models of import to organizational function, among everyone. One employee may intellectually support the mission but it may lack emotional resonance and hence inspirational power for him. So variation in adoption and adherence to mental models is the norm. Certainly it is normal and in some cases might be beneficial to have variation in many of the less consequential parts of one’s organizational culture (e.g., how to run a meeting).

The key is that your most important mental models must be understood and jointly held in the hearts and minds of the group. The strength of a company’s culture is a function of how widespread and deeply ingrained those mental models are. Deeply ingrained mental models, in turn, should drive behavior, both directly and indirectly.

Your organization’s vision and mission and your core values (if you have them)—these are not just statements and lists, they are mental models that need to be built by everyone in the organization. If you want to build culture, build and share your mental models. Here are numerous words that are roughly synonymous to culture, including: ideology, climate, values, beliefs, traditions, and norms. If you are wed to using one of these words to talk about your company, you needn’t despair. All those things are mental models that, when shared among group members, constitute organizational culture.

Leading Organizational Change Is a Culture-Building Campaign

Quick pop quiz! Organizational change is:

- Easy

- Hard

If you answered 1 you either work in an organization composed of 1 person, have never tried organizational change, or are an organizational genius and need not read any further. If, like most of us, you answered 2, here’s why: command hierarchies don’t actually work as promised. If they did, controlling organizational behavior would be easy. All you’d have to do is decide at the top how things should be and then pass it down the hierarchical chain. At each level of hierarchy each person would do exactly what their boss wanted and presto! We’d have the desired organizational outcome!

McKinsey reports that 70% of change efforts fail, largely because of employee resistance and lack of management support. But guess what: half the battle of organizational change is cultural change. In fact, we’d venture so far as to say that it is impossible to meaningfully change an organization without changing its culture, its shared mental models.

The reality is that most folks reading this book do not have the luxury of setting direction for a startup organization, and therefore must be concerned with the issue of changing a pre-existing culture. Even in new organizations, leaders will have to contend with diverse pre-existing mental models (biases) of its employees. A recent article described the approach many CEOs take when confronted with the need to change their company’s culture.

They turn up the volume on the inspirational messages. They raise the bar and set stretch goals with new statements of the vision, mission, values, and purpose of the company. They bear down on costs and castigate people for complacency.

Alternatively, they delegate the task to experts. Either way, these approaches are rarely successful. And while things like company slogans and logos can be changed easily, the deeper elements of culture take much more time and effort to build and alter.

Katzenbach and Aguirre offer sage advice about cultural (organizational) change.

Demonstrate positive urgency by focusing on your company’s aspirations—its unfulfilled potential—rather than on any impending crisis. Pick a critical few behaviors that exemplify the best of your company and culture, and that you want everyone to adopt. Set an example by visibly adopting a couple of these behaviors yourself. Balance your appeals to the company to include both rational and emotional cues. Make the change sustainable by maintaining vigilance on the few critical elements that you have established as important. In all this activity, avoid delegating your culture-oriented actions. Do as much as you can yourself.

Another critical task is to visually and behaviorally represent (rather than just verbally articulate) the core tenets of the old culture and the new mental models that will take their place. This unlearning process is the definition of leadership—taking people from the undesirable or suboptimal present to the desired future state (i.e., the vision).

Your Organization Is a Network, So Choose a Suitable Change Model

The network structure underlying groups and organizations of all types is conducive to a systems approach based on complexity science. This is because collectives of individuals, no matter how structured, are complex adaptive systems.

Irrespective of their formal structure—rigid formalized hierarchy, fluid and minimalist structure, or somewhere in between—all organizations are made up of the networked interactions of individuals (agents) who adapt to and learn from an environment. All organizational structures are overlaid on a network of semi-autonomous individuals. In short, VMCL provides a model that corresponds with all organizations—formally structured or not—because it focuses on their underlying structure and network behavior.

Network theorists have contributed substantially to our understanding of social change, influence, and contagion processes—all of which are germane to culture building. A recent study demonstrated that a small group of diehard proponents of an idea or position—just 10% of a population—can sway the majority of society who hold a contrary opinion but are open to other views. The 10% represents a tipping point after which society rapidly converts to the new mental model, and this occurs across several different network structures. Other work on collective action emphasizes that considerable change is often achieved in groups by just 5% of members. Building on these insights and recognizing the inherent difficulty of changing hearts and minds, our model focuses less on achieving immediate group-wide adoption and instead offers a process for incrementally building support for a culture. This change effort—the process by which mental models are spread organization-wide—is best represented and tracked by a culture-building graph (CBG).

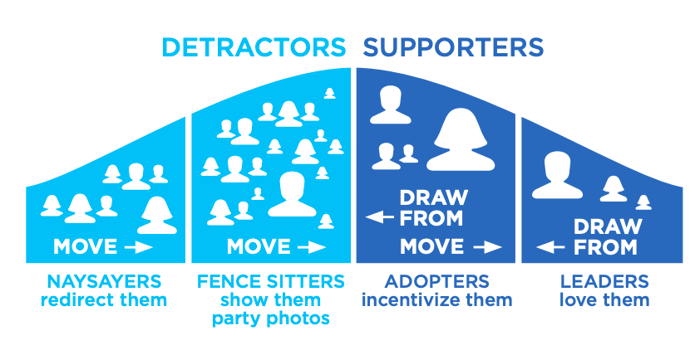

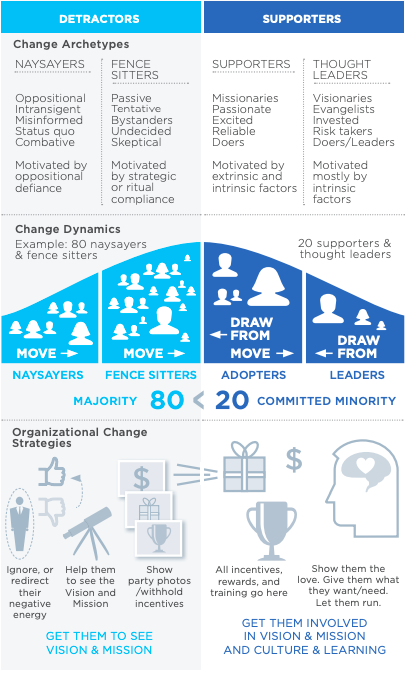

Figure 1: Culture-building graph

A CBG is a tool for organizational change that demarcates who is on board with the organization’s key mental models and who is not (and to what degree). While the distribution of support in your organization is unlikely to fit a bell curve, you can often expect a smaller number of ardent opponents (“naysayers”) and ardent proponents (“leaders”) of organizational culture.

Remember the CBG is not a compliance model, it’s an indication of your progress in inculcating culture; that is, your progress in teaching (indeed, selling) mental models. CBGs help identify work that needs to be done to make the shift toward a new organizational culture. CBGs can be used in the same way that a Senate Majority Leader might place images of senators in the Yay or Nay column in preparation for a vote. Placing individual employees on the CBG helps leaders know where the work needs to be done and how to adequately teach, motivate, and incentivize each individual. Incentives, of course, needn’t be monetary; in fact, they are ideally intrinsic (hence your job as chief culture officer/mental model builder for your team). As Visa credit card founder and CEO Dee Hock wrote, “Money motivates neither the best people nor the best in people. It can move the body and influence the mind, but it cannot touch the heart or move the spirit; that is reserved for belief, principle, and morality.”

And remember that the formal title and position of an employee says little about where they reside on the CBG. The Clemmer Group asks in a blog: “Are vision, mission, or values just words from above or do they vibrantly live in all key people decisions like hiring, promotions/succession planning, recognition/appreciation/ celebration practices, and tough actions like discipline or letting someone go?” Your lower-level leaders are likely to vary in their support for and implementation of your culture. “Departmental or division managers can shape their culture (leading), sit back and wait for direction from above (following), or throw up their hands in frustration at executives’ lack of culture leadership (wallowing).”

Figure 2: Culture-building graph archetype strategies, download the poster here.

Figure 2: Culture-building graph archetype strategies, download the poster here.

Leading Each CBG Group

On the right side of the CBG are culture adopters and leaders. These folks support cultural pillars. On the left side of the graph are non-supporters: fence sitters and naysayers. The idea is to manage the process of getting as many people as possible from the left to the right side of the graph, thereby creating a critical mass of support. As one might imagine, culture leaders in the organization typically don’t need much more than camaraderie and appreciation to continue their work advocating the culture. We generally give them love and support. We enlist them as cultural ambassadors and hold them up as examples. You do not need very many senior leaders to start a few critical behaviors rolling through the company. As Katzenbach and Aguirre suggest:

Get several well-known executives to step away from the norms of the past with you. People throughout the workforce will rapidly take notice and do the same, creating an atmosphere of approval and support. In short, by seeking out other early adopters of these behaviors, and working with them directly to sharpen their influence and deploy it more effectively, you will gain far more leverage as a cultural leader.

The majority of those who buy into the culture can be called adopters, and this group is where your incentives and rewards should go to effect change. While they exhibit compliance, can you discern the source? Is it ritual/habitual? Strategic and therefore more precarious? Or do the adopters embrace the organization’s key mental models? Obviously, this begins with ensuring deep understanding among group members of the VMCL. But to be clear: this is where you focus most of your time and other resources.

Let’s talk about the left side of the graph, the two groups that are not fully on board. Ironically, while adopters are the proper target of your resources, we will devote more ink to non-supporters. Organizational leaders often make the mistake of rewarding fence sitters to entice them to move to the right (toward cultural leader), which ironically only serves to motivate fence sitting. Fence sitters are waiting to see what’s going to happen, so you want to avoid rewarding this behavior. But you also want to teach them and show them the benefits of joining the culture. Do this by showing them what we call “party photos”—assorted communication through various media that convey to fence sitters that the side of corporate culture is the place to be—they’ll get rewards, have fun, have a sense of purpose and belonging, and love what they’re doing. Resist giving fence sitters any rewards, show them party photos, and scrupulously avoid getting in control battles with them.

Naysayers, a veritable fact of life for new leaders or reformers, require a different strategy. They can be a heterogeneous group, so the first step is to learn their grievances, as they may have very legitimate complaints. In some instances, you can move naysayers to become culture proponents. Other times leaders may simply confront staunch opposition to change. In such instances, they should focus on redirecting the naysayers’ energy and not letting them set the agenda with their opposition. Having earnestly entertained their grievances, leadership must refocus its efforts on other group members.

Do not simultaneously discuss mission, capacity, and learning with naysayers. Focus first and foremost on the vision. Why? The organizational vision is often less controversial than the tactical and strategic considerations that come with deciding mission, capacity, and learning for an organization. Say you lead a company that makes products that facilitate environmentally friendly behavior on the part of consumers. As a group, you come up with a tentative vision of “Doubling recycling and composting in metropolitan areas.” You want to do this through a mission—admittedly loosely defined—of “Making it easy to do the right thing.” Your leadership team is instituting plans for capacity and learning and identifying key mental models that will constitute culture while ensuring the alignment of your VMCL.

You face a small but vociferous cadre of naysayers. So you focus on the vision: “Are you against doubling rates of recycling and composting?” If the answer is no, we know there’s a chance we can move them toward being cultural proponents. If the answer is yes, then it becomes clear that the naysayer (1) is a poor fit for the organization, (2) has some relevant and important position that should be considered, and/or (3) may adhere to their opposition no matter what you do. Anyway, once agreement is achieved on vision, discussion can move to mission (repeated steps to achieve the vision). If agreement is achieved there, discussion can proceed to culture/capacity and, eventually, to learning. Effective leadership moves incrementally toward building understanding, support of, and adherence to shared mental models; that is, it shifts the group to the right of the CBG.

With time and perseverance, you may succeed in building a cult-like culture. !e word “cult” is not without negative associations, but hear us out. Cultures become cult-like when a vast majority of the organization fervently believes in and is passionate about the organization’s key mental models.

Research and management guru Jim Collins explains that organizations become great when they face the brutal realities of their business and build a focused culture. He calls these cultures "cult-like" because they have a rigidly enforced set of cultural norms (even if the norms themselves are flexible). In other words, those individuals who don't fit, don't want to be there, and those people who do fit, love it. As an organizational leader, it’s your job to build this cult-like culture by teaching and inculcating your key mental models.

.png?width=150&height=150&name=CRL%20GOAT%20Logo%20(4).png)