8 Things We Can Learn About Systems Thinking From The Coronavirus Crisis

As we enter week three of social isolation [1] , I am reminded, and frankly a little surprised, at just how important the ideas we teach are. You see, as a professor you take a lot of grief about being out of touch, too abstract, too theoretical, too impractical, too “head in the clouds.” As a theorist, this happens even more so [2] . As a systems theorist, even more so than that [3] . So, despite the trying times that we all find ourselves in, it is somewhat of a comfort that the things that we teach our students everyday in “normal life” turn out to actually matter.

It turns out that, like a good pair of boots, science and theory are something that many of us are forced to face when we’re in a crisis. In contrast, these ideas seem optional during “more comfortable” times (although they, in actuality, are not).

And, nowhere is this “optional” consideration of science more tangible, more palpable, and the contrast more cognitively dissonant than in the daily briefings offered by the President and his Coronavirus team.

Let’s review just a few of the things we teach in our graduate course on systems thinking that provide insight into this crisis and the necessity of the ideas we teach to graduate students in public affairs:

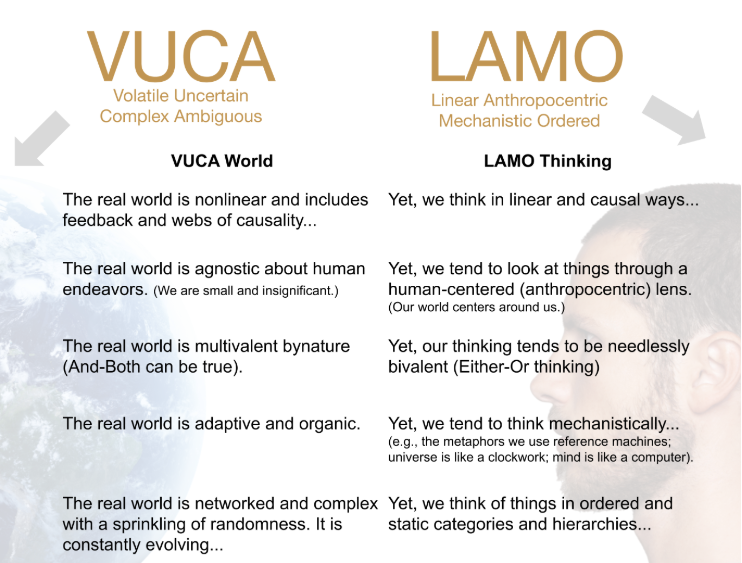

The world is VUCA but our thinking is LAMO and the resultant misalignment presents many problems.

It’s not a problem that the world is VUCA (Volatile Uncertain Complex Ambiguous). The problem is that while the world is VUCA, the way we think about the world is what I like to call, LAMO -or Linear, Anthropocentric Mechanistic and Ordered. Our thinking is biased in ways that don’t match up with the way the real world actually is. We project this bias onto the world and as a result, often miss the critically important feedback the world is giving us that would help realign our thinking with the way things actually are. For example:

- The real world is nonlinear and includes feedback and webs of causality...Yet, we think in linear and causal ways.

- The real world is agnostic about human endeavors. (We are small and insignificant.) Yet, we tend to look at things through a human-centered (anthropocentric) lens. (Our world centers around us.)

- The real world is multivalent by nature (And-Both can be true). Yet, our thinking tends to be needlessly bivalent (Either-Or thinking)

- The real world is adaptive and organic. Yet, we tend to think mechanistically... (e.g., the metaphors we use reference machines; the universe is like a clock, which it is not; the mind is like a computer, which it is not).

- The real world is networked and complex with a sprinkling of randomness. It is constantly evolving...Yet, we think of things in ordered and static categories and hierarchies.

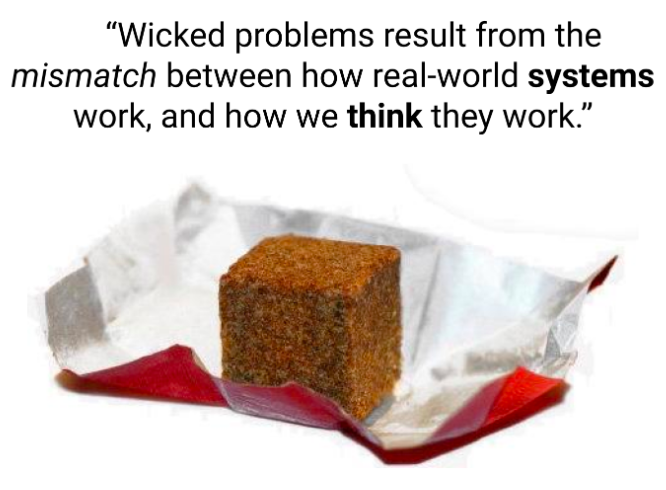

Wicked problems and the reality of a VUCA world require us to change our thinking from LAMO to systems thinking.

Ritel and Weber in 1973, coined the term “wicked problems.”

- They are characterized by multiple and fuzzy boundaries. We often don’t know where these boundaries begin and end.

- They are highly interconnected. Many interlinked issues, cutting across the usual silos (e.g., economy, health and environment), making for a high degree of complexity.

- They exist on multiple time and physical scales. Multiple agencies (across the public, private and voluntary sectors) trying to account for multiple scales (local, regional, national and global problems).

- Our solutions can breed new problems.

- Often a solution can only improve a situation, not resolve it entirely. Often we solve the issue by improving a situation, only lessening the effects of a problem.

- Many perspectives (sometimes conflicting ones) exist on the problem. Many different views on the problem and potential solutions. Conflict over desired outcomes or the means to achieve them, and power relations making change difficult and intractable.

- The problem can vary by context.

- Decision makers need to be responsive and adaptive.

- There are multiple and serious human costs. There is uncertainty about the possible effects of action on humans.

- They are often not formulaic. There is no template solution.

If this list doesn’t speak to the seriousness of the Coronavirus crisis, I don’t know what would.

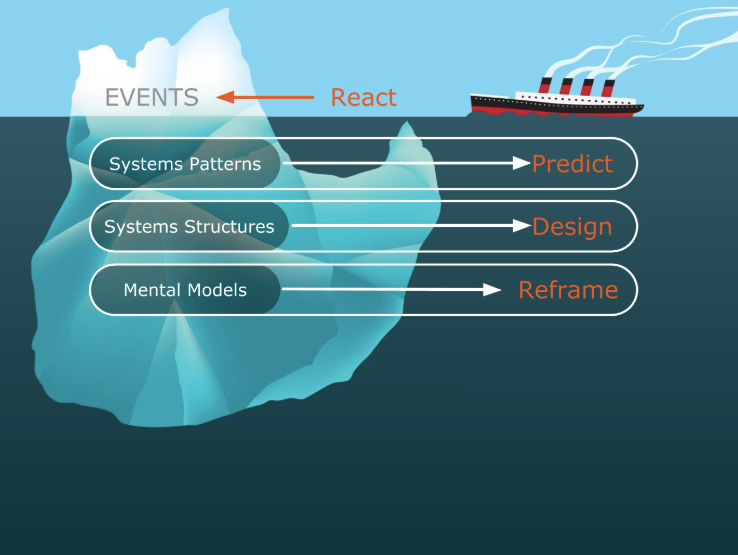

We must look beneath the surface to see the complex reality of the natural world, and uncover the patterns, systems structures and mental models underneath.

Systems Thinkers look deeper. And then deeper again. Systems thinking highlights the tendency humans have to ignore deeper patterns and structure because we are enamored with surface-level details and events. So, systems thinkers go beyond the surface features to look at how the world works and also how we think about it.

We can think of the real VUCA world as an iceberg —there’s more to it than meets the eye.

You—or your organization, hospital, city, state, country—are the boat (hopefully not the Titanic). This focus on the superficial events often means that our only response is to REACT to them.

Systems Thinking encourages us to think deeper so we can do more than just react to events. When we look deeper at a situation or event - to find the underlying systemic patterns (repeating events, etc) - we can PREDICT what’s going to happen before it happens. Often, this gives us precious seconds, minutes, days, weeks to respond more thoughtfully.

If we go deeper still, we can see the underlying structure of the system. A popular moniker in the field of systems thinking is: system structure determines behavior— that is, the way systems are organized will actually determine their behavior. The way this coronavirus is structured determines its behavior. The way we are structured determines our behavior. The way we structure the response, will determine our collective behavior. When we learn to see these underlying systems structures — we can DESIGN system structures to bring about the desired behavior.

Systems thinkers to look at our inherent biases in the way we frame our mental models When we ACKNOWLEDGE and CHALLENGE these mental models, it allows us to see ways to totally reframe the event and see it in a different way. In other words, as Einstein said, “We cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.”

The problem has been, prior to deeper studies in neuroscience and cognition, we didn’t really understand how mental models were built, nor how they aligned with real-world systems structures. Today we know quite a bit more about mental models and how they work.

When we see the underlying cognitive code (see below - DSRP) that structures our mental models, we can TRANSFORM how we frame, design, predict and react.

People are biased and their mental models govern how they behave, act.

One example of bias that affects our mental models is confirmation bias which causes us to filter real-world information to fit our mental model, rather than to fit our mental model to the real world.

In order to even consider that the goat is not in a cloud--that the mountain goat is most likely where goats normally are, on the side of a mountain--we need to consider that it might be just a mental model, not reality. This means we must acknowledge mental models. So, we desperately need to understand:

- The reality of mental models;

- The language of mental models;

- The skill building, sharing, and evolving of mental models; and

- The technology to support it in organizations.

The opposite of bias, is to fit your mental models to reality rather than reality to your mental models.

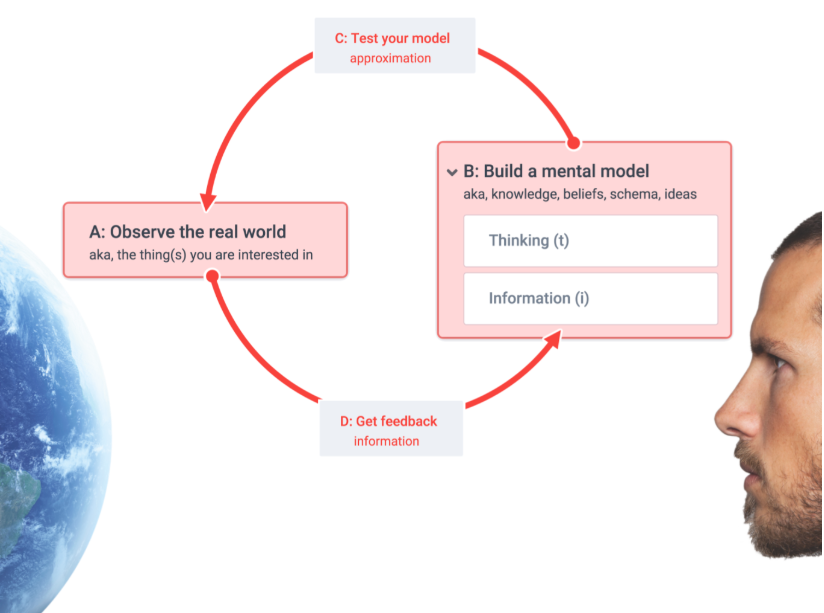

And this brings us to the CRUX of systems thinking: The ST LOOP.

- Observe the real world.

- Build a mental model.

- Test your model against the real world

- Get feedback /information.

- Start the LOOP again: interrogate and evolve your mental model.

And, it's a loop, so you must go around and around it! Each time you do, your mental model gets better! And better. A better approximation of reality. Because the CRUX of ST relies on this process, it becomes very important to understand precisely what mental models are made of. They are not merely made up of information (which comes from the real world and past experience). But are also made up of how we structure, organize, or encode that information. This is called thinking or cognition. We can summarize mental models in a simple equation:

M = i + t

M or mental models is synonymous with knowledge, meaning, what I think, ideas, conclusions, etc.

i is synonymous with data or content.

Whereas, t or thinking is synonymous with how we structure, organize, encode information.

Mental models are made up of information and how we structure that information to give it meaning. When we structure information differently, we get different meanings. The key to systems thinking is understanding the t, as the information will be variable.

We teach that, as the statistician George Box once said, “All models are wrong, but some are useful.” The quality of your model is based on the quality of the information (real world data) and the veracity of one’s thinking.

This simple ST loop is also profound. It demonstrates that systems thinking (done well) is no different than science (done well). Indeed, historically, systems thinking emerged as a criticism not of science itself, but of the way science was increasingly “being done” in careless ways, such as:

- Too much focus on reductionism and not enough on holism (i.e., the need to balance the two);

- Too much reliance on linear-causal studies and not enough on developing an understanding of webs of causality;

- Needless adherence to disciplinary norms, when the real world is interdisciplinary;

- The tendency to remove/isolate variables from their more complex context (often with good intention to reveal new insights), but then failing to remember this all-important context; and

- A failure to recognize the importance of mental models (bias and “objectivity”) as determinants of agent-level action and system-level behavior.

In short, teaching systems thinking is synonymous to teaching a scientific approach to life. We all need to approach the real-world with a scientific mind, where data, facts, reality, and thinking trumps opinions, hunches, and feelings.

CASs are uniquely structured and have unexpected effects...

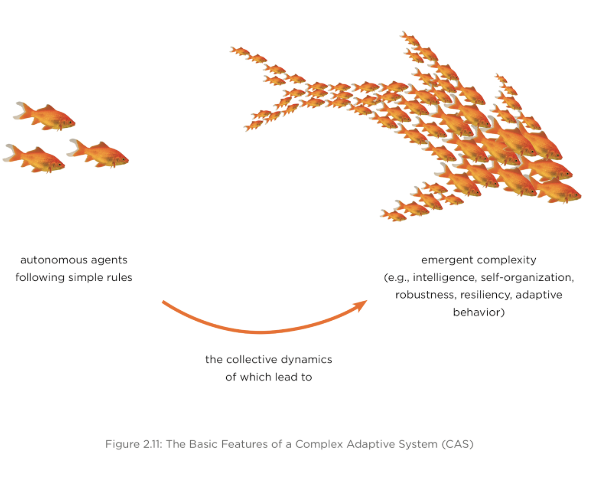

We teach that complex adaptive systems or CAS, are uniquely structured. Even though they can produce surprising behavior (like doubling effects, or intelligence, etc), this behavior is an emergent property of the collective dynamics of local simple rules and autonomous agents.

What does this mean? It means that our response to this virus globally is dependent on the simple things that we all do locally.

The unexpected effects of CASs are often quite predictable; based on understanding the agents, the simple rules, and some basic math.

It means that many things we are seeing with Coronavirus are predictable:

- The growth in the numbers of people being infected;

- The growth in the numbers of people dying; and

- The number of respirators, masks and EPPs needed.

Indeed, the math is pretty simple. Let me give you an example. President Trump criticized (indeed openly disbelieved) New York Governor Andrew Cuomo’s stated need for 30,000-40,000 ventilators. But math isn’t political, it’s just math.

As of March 30 at 9:41 p.m. ET. New York reported at least 66,497 total positive cases of COVID-19. They are also reporting that the numbers are doubling every 2-3 days.

- In 3 days that means there will be: 66,497 x 2 = 132,994 cases

- In 6 days that means there will be: 132,994 x 2 = 265,988 cases

- In 9 days that means there will be: 265,988 x 2 = 531,976 cases

It is estimated that between 10-15% of the cases will end up in the ICU where a ventilator will be necessary. This means that in 9 days the 531,976 cases will see 10% (or 53,197.6) in the ICU and in need of a ventilator. Yes, there will be some overlap in ventilators to ICU patients (as well as deaths, etc), but given that the virus lasts for several days, the 30,000-40,000 is predictable. And it requires little more than multiplication, and an understanding of the key relationship between local agent’s choices and collective impact on the system.

It is also quite predictable that:

- 15 cases will not magically reduce to zero;

- This will not be over soon;

- We will not be able to resume normalcy by Easter;

- Significantly more people will die if we do not practice social isolation; and

- As the scientists have said, “Between 100,000 and 200,000 people will die if we do everything near perfectly.”

Suffice to say, if you are fitting your mental models to reality rather than forcing reality to fit your mental models, there is much about this crisis and this virus that is wholly predictable.

The distinctions (D) you make matter. Seeing how systems (S) are organized matters. Seeing the interconnectedness (R) of systems matters. And, perspective (P) matters.

We also teach a lot about how DSRP helps us better align our mental models with reality. We teach that the distinctions you make matter.

For example, when something is called a hoax and people believe that it is, that mental model will influence their behavioral choices. After all, if you believe it's a hoax, you might not take coronavirus seriously and continue about your normal day by disregarding the need for social distancing. Thus, contributing to the further spread of the disease.

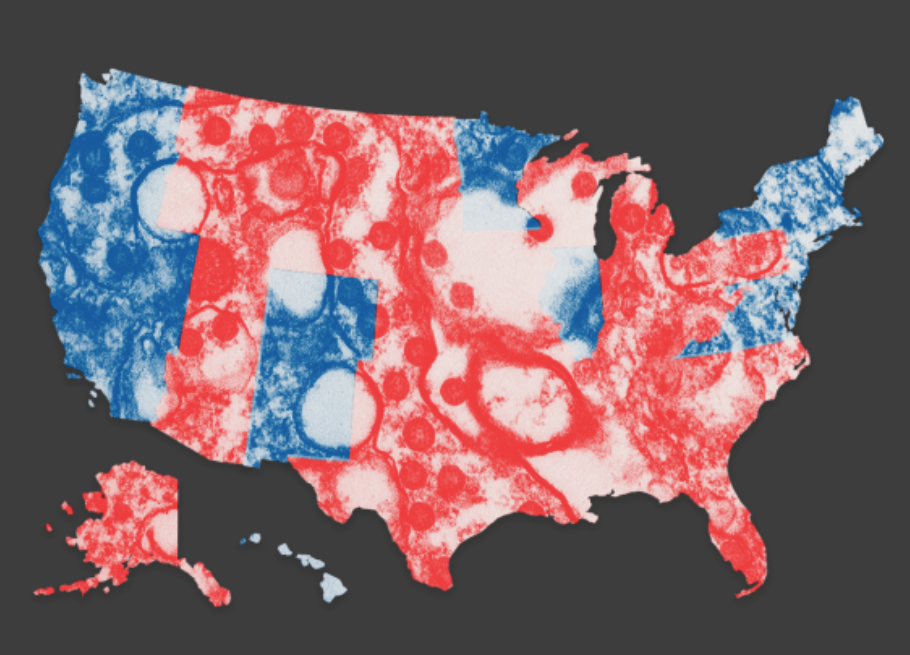

For example, “Overall, although the number of detected cases is higher in blue states, the number is increasing at a more rapid rate in red states [4] .”

What explains this? Blue states have a higher number of reported cases because (1) blue states tend to have high population densities and (2) people in Blue states don’t believe that it is a hoax and therefore are testing more. Red states, where their mental model is like Trump’s, aren't testing as much and have fewer reported cases despite the fact that they are growing at a higher rate than blue AND they have less population density!

If a President you adore and trust tells you this and you believe it, then what we might see from those millions of agent behaviors is a higher spread in rural Republican areas where the structure of the system would not warrant that (ie. the low population density). In Democractic areas that tend to be more populated you would see higher rates of contagion due to the structure of the system: specifically its population density.

Or, if you have a mental model that the virus only affects old people and compromised people, you might go party on the beach for Spring Break when you should be quarantining. Then you spread the virus across the entire Eastern seaboard when you fly home.

Want to see the true potential impact of ignoring social distancing? Through a partnership with @xmodesocial, we analyzed secondary locations of anonymized mobile devices that were active at a single Ft. Lauderdale beach during spring break. This is where they went across the US: pic.twitter.com/3A3ePn9Vin

— Tectonix GEO (@TectonixGEO) March 25, 2020

Or, if the President tells people that he “had a feeling” that the drug hydroxychloroquine helps to combat coronavirus despite no data to support this feeling, this may cause your supporters to share this false mental model and immediately go out and buy up all the supply leading to unintended consequences like death or (on the off chance that your hunch turns out to be proven later on) making it so that the health care system no longer has an adequate supply of the drug.

In our 16 week course, we focus 15 weeks on teaching how DSRP is foundational to better understanding and doing systems thinking.

Finally, what we all do matters. And, that as a result of this, we cannot leave systems thinking to the experts. We must all do it. Especially politicians & Presidents.

Systems thinking is a call to arms that we all must do.

A manifesto to think more scientifically, more systematically, more contextually, and more about ourselves in the context of others. We teach the systems thinking manifesto:

We are all literally in this together. Let’s start thinking like it.

-

I say “isolation” rather than distancing because (1) I think it’s far more accurate and (2) as our “compromised” grandparents have moved in with us, we have formed a very tightly managed bubble around our house to ensure that they are not exposed. ↩︎

-

Even though Kurt Lewin’s statement that, “there is nothing more practical than a good theory” is true, many folks have real difficulty understanding what a theory is (hint: it's not a hypothesis) nor understanding the idea that if what you do doesn’t work in practice, it's because you’re theory is wrong or you don’t have one. ↩︎

-

Try explaining that you’re a systems scientist and theoretician at a neighborhood BBQ for example. ↩︎

-

From FiveThirtyEight's "The Coronavirus Isn't Just A Blue State Problem." ↩︎

.png?width=150&height=150&name=CRL%20GOAT%20Logo%20(4).png)