Let's drop the dualities in systems thinking.

I would simplify matters by saying that ontology essentially means reality or the real world, while epistemology can be thought of as our mental models, or what we think we know about the real world.

I should also say that I think these debates are especially ironic when it comes to systems thinking, because systems thinking, at its core, eschews the binary logic that leads to such dualities. All such dualities inevitably live inside of context. This context is multivalent, complex, and rich.

One reason duality (contrasting mental models vs. the real world) is somewhat silly is that as evolutionary beings, our bodies and our minds have evolved inside of the constraints of the real world and its determinant physical laws (e.g., gravity), and in that sense our minds are reality-processing machines. Hence, reality and the mind are tightly coupled.

By way of an analogy, consider that recent studies in the field of gravitational biology reveal that our bodies cannot build muscle in zero-gravity, not because it's not technically possible, but because our bodies evolved within the context of gravity--they know gravity. This has some important implications: it means that there are a few things we might say that are not in fact so.

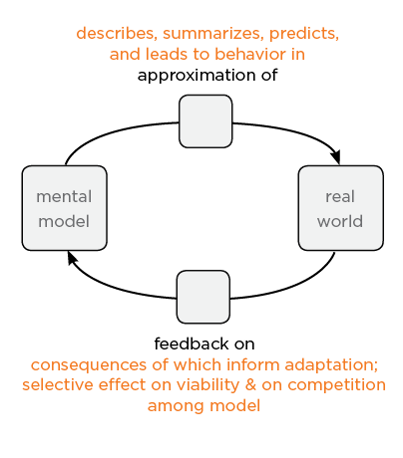

For example, if one (e.g., a positivist) were to say, "I believe we can know the objective truth about the universe." Well, not really. We are never 100% certain that our mental models are right. In fact, if we are doing things right we are constantly learning and therefore our mental models are evolving and in tiny incremental steps we are learning to make them more right. But they are never truly "right."

For a second example, one (e.g., a postmodernist) might say, "We cannot know anything. We don't know anything about ontology/reality because we cannot know reality." This too is a bit hyperbolic. We can know things about reality because we are a little slice, a part, of reality. Our minds evolved to capture a slice of it--to approximate it with our mental models.

- Mental models (epistemology) approximate the real world (ontology)

- Science is merely a process of validating mental models that better approximate the real world

- As George E.P. Box said, “All [mental] models are wrong; the practical question is how wrong do they have to be to not be useful.”3

- The mind itself is embodied

- The mind and the body are born of evolutionary processes. They are not separate from reality but part of it.

Footnotes 1. Drawing Hands by M. C. Escher, 1948, Lithograph. From The Magic of M. C. Escher. Harry N. Abrams, Inc. ISBN 0-8109-6720-0↩ 2. Cabrera, D & Cabrera, L. (2015) *Systems Thinking Made Simple: New Hope for Solving Wicked Problems*. Odyssean. p. 65↩ 3. Box, GEP & Draper, N.R. (1987). Empirical Model Building and Response Surfaces (p. 424). New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.↩

.png?width=150&height=150&name=CRL%20GOAT%20Logo%20(4).png)