Slider: Integrity vs Duplicity - An Interview With Dr. Derek Cabrera

Staff

·

7 minute read

Staff

·

7 minute read

This post is a part of the ongoing Slider series. Find more like this one here.

[Staff] You talk about mental models a lot in our work. And, you also talk about the importance of integrity as a character trait. I know that you have developed a slider called Integrity versus Duplicity. Could you share a bit about this slider?

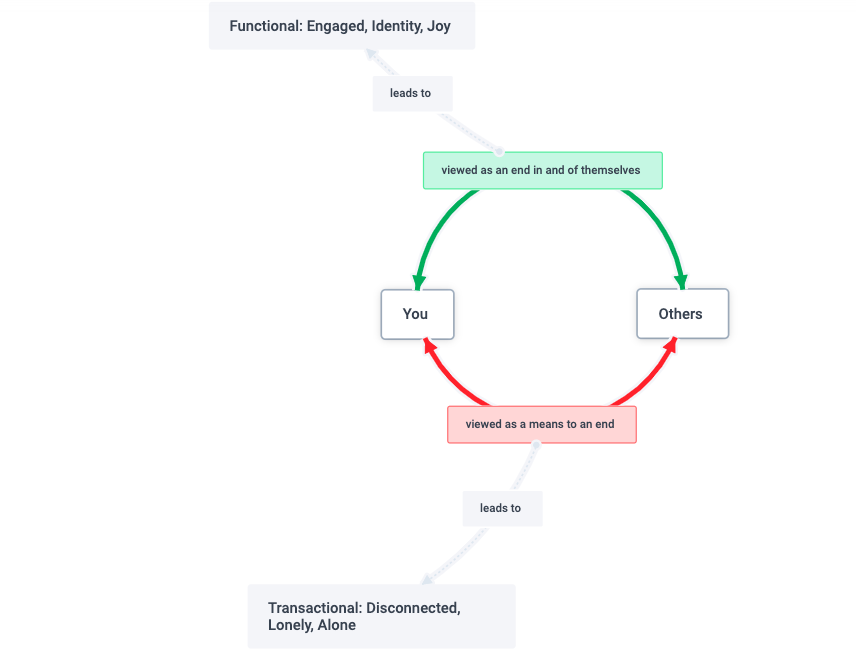

[Dr. Cabrera] Sure. The Distinction rule allows us to deepen our understanding by comparing and contrasting the identity and the other. That is, whenever we consider the meaning of an idea (its identity) we also must consider the meaning of the other ideas that it is not (but are proximally or distally related). For this slider, in order to gain a deeper understanding of integrity one must also consider the meaning of duplicity.

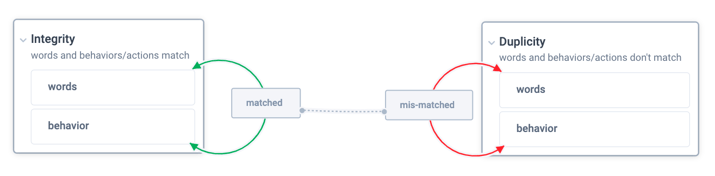

Integrity means “a state of being whole and undivided.” When something lacks integrity it is divisible, dividable, breakable into parts, in a way that do not cohere into a whole. By definition then, integrity also means “not duplicitous.” Duplicitous, on the other hand, comes from the word duo (meaning two). Duplicitous implies there are two things: what one says, and what one does. To be duplicitous means that your words say one thing and your actions say another. This is the fundamental definition of duplicity.

If we utilize this understanding, we recognize that integrity is the exact opposite of duplicity. Integrity is that your words say one thing and your actions say that same thing. When your actions and words match, you have integrity. When there is a mismatch between your words and actions, you are duplicitous.

There’s a common misconception about what integrity means. What comes to mind for a lot of people when they hear “integrity,” is being honest or telling the truth. Being honest to them means saying the right answer. But, what integrity really boils down to is matching what you say and what you do.

This means that you can have a “bad” or devilish person who has impeccable integrity. For example: Charles Manson. When Charles Manson was interviewed on television he was asked, “What would you do if you were let out of prison?” He answers, “I would kill again.” In a sick way, that is integrity. His words and actions match up, and people believe him because of it.

[Staff] So when you’re listening to someone speak, are you focused more on their words or more on their actions or both?

[Dr. Cabrera] Well certainly its both and in particular it is about the match or mismatch between them. But I think it is super important to understand what we mean when we talk about what a person is saying. Because we often think of what a person is saying as the words they are speaking. And it is, but that is just half the equation. Their actions are also speaking for them and their actions are “saying” a lot as well. So I’m asking, “what do your words say?” but also, “what do your actions say?” Because both of them are saying something. And then I’m asking myself, “Are they saying the same thing?”

And I go so far as to convert actions into sentences. What would the sentence be that speaks for your actions? And that’s not just for your communications with other people but with yourself as well. What am I saying when I behave that way?

[Staff] So you take the behaviors that you are doing and then you match your words to those behaviors?

Or vice versa. I mean, it's really an interaction effect between words and behaviors or words and actions. That’s what we mean when we say that someone has integrity, it means that you can trust that they're going to say what they do and do what they say. We sometimes miss the first part of that idea. We focus on whether people do what they say. But do they also say what they do. There’s a lot of duplicity that goes on by selective honesty. We might do what we say and yet there’s still a lot left unsaid and a lot of things we do that we don’t talk about. So, is that personal integrity. Only we can hold ourselves accountable for that kind of thing.

So that means that if a person has integrity and they stole a cookie out of the cookie jar and you ask them directly, did you steal a cookie, you would expect that person with integrity to say, yes, I took a cookie. And if a person says, if you say that one more time, I'm going to sock you in this in the kisser then you would expect that if you say that one more time, that person is going to sock you one. Those are all examples of integrity. Now, of course, we know those are kind of both negative examples of integrity, but there's all the positive examples of integrity. But integrity in and of itself doesn't mean positive. It's positive in one way, which is that there's not duplicity. But it could be integrity about, you know, a crime.

And of course, if I stole ten cookies and you ask me did I steal a cookie and I say “yes;” That’s not really integrity either, because although I did do what I said, I didn’t fully say what I did. I said I stole one cookie. And I did steal one cookie. But I neglected to mention that I stole one cookie ten times.

So integrity is a feedback loop that goes both ways. And, it could be integrity about lots of different things. And, integrity can be intrapersonal or interpersonal.

[Staff] So these examples are new to me and fascinating. It appears that one has the chance to be either be duplicitous or have integrity in every sort of micro choice they make throughout their daily life.

Absolutely. That’s how dynamic integrity is. And this insight becomes critically important when we talk when we talk about DIY self-help, which is what sliders are really fundamentally for.

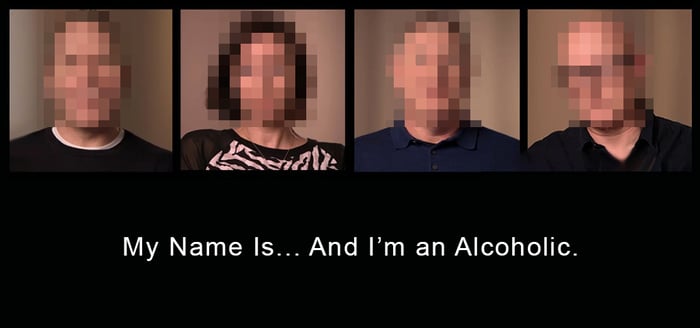

Integrity becomes really critically important, especially in these negative examples. I hate to keep using negative examples to describe integrity, but it turns out that it actually becomes incredibly important. So I'll use the example of Alcoholics Anonymous. I mean, the first thing that an alcoholic or a drug addict has to do is to recognize their behavior in words and say, “I’m Bob, I am an alcoholic.” Until that step, they can't take the subsequent steps of fixing the problem because they haven't put the problem into words. They haven't been honest. They haven’t looked in that metacognitive mirror and put a label on their actions.

Now everybody around them knows what their actions are, right? But it's hard to get them to admit. And so it's hard to get them to change, right?

Now everybody around them knows what their actions are, right? But it's hard to get them to admit. And so it's hard to get them to change, right?

So if you're thinking from a DIY self-help perspective and a Slider's perspective—if you're trying to develop yourself...make yourself consistently, incrementally better over time— a huge part of that is just coming to terms with the things that you're doing. So, you know, if you're not exercising enough, then, “hey, you know, I don't exercise enough.”

Or if you’re always telling people things are “fine” when they ask. Well, maybe you’re not “doing fine.” You know, “doing fine” is one of the worst duplicitous statements in your own developmental trajectory. “Everything's fine.” “I'm fine.” You know, that's the beginning of duplicity because things are not fine.

So, you know, the core of this thing is being okay with putting actions to words and words to actions. And sometimes you might say something and you go, “well, I would never follow through with something like that. I would never act in that way.” OK. Well, why are you saying it then? And, the reverse is also true. So sometimes you do something and you say, “I would never want to put that into a sentence!” OK, well, then why are you putting it into action? And remember that you are putting it into a sentence because your actions are a living breathing sentence. Your actions speak louder.

The point is that there's a spooky balance between words and actions where the one sort of forces you to see the other. And and if either one is unacceptable, then both should be.

If carrying out the actions of certain words would not be unacceptable, then maybe the words should be changed. And, if putting your actions into words causes you to be a little embarrassed or ashamed then maybe the actions need to change.

[Staff] So you can use this slider as sort of a stepping stone by matching your words and behavior or at the very least using the slider to fix either small or large problems that you have either with yourself or your relationships.

Absolutely. And if you think of it as a continuum of health, of functionality. A person whose words and actions don't match is not as far along as a person whose words and actions do match, even if those words and actions are a little bit, you know, undesirable.

And it is much harder to help someone with a maladaptive pattern who is duplicitous than it is to help someone with a maladaptive pattern that has integrity. If someone does things but can’t admit them, that's a much harder situation to deal with than when you have somebody that's like, “yeah, I do this all the time and it really bugs me, and I really want to fix it. And I don't know how to. I haven't figured that part out yet. But I am clear on you know, I don't like the way that I'm behaving in this situation. And I can I can identify it. I can label it. I can admit to it. I can talk to it.” That's a much easier case to deal with.

[Staff] Yeah, once you can admit it you can take the next steps... So you can kind of relate this idea with the systems thinking loop of matching your mental models to reality.

Totally, because with duplicity, you're not existing in reality totally. And in a sense, that is fundamentally what the ST Loop is all about. The ST/DSRP Loop is all about getting that match between reality and your thinking and similarly, the Integrity Slider is all about getting that match between words and actions.

And so it is just a fractal version of a match between the reality of your behavior and the reality of your words, both of which are derived from your mental models. Which is critical to understanding human nature because there is a kind of “universal integrity” that can be assumed that we can see a throughline between one’s mental models, their actions, and what they are saying—notice I didn’t say their words, but what is being said. So we can sort of know from people’s actions what their mental model is and we can also let their actions speak for them.

And and, you know, go find a developmental program that works. And I will guarantee you that somewhere in that developmental program is that metacognitive state of sort of accepting the truth, accepting the truth of your behavior, accepting the truth of your condition, accepting that, you know, becoming aware to the point where you can put it into words of your actions.

.png?width=150&height=150&name=CRL%20GOAT%20Logo%20(4).png)