Systems Mapping: Applied Systems Thinking

I’ve studied Systems Thinking for thirty years in one way or another. Formally for 20 of those years. When I first came to the formal field of systems thinking I was both energized by its potential, a little skeptical of its claims, and frustrated by what I saw as a dearth of practical and accessible applied tools that systems thinkers could use not only to solve “wicked” or complex problems, but to understand and solve everyday problems as well.

First, I set to work on the concepts of systems thinking. I often tell audiences that I was a bit like the little baby bird in Dr. Seuss’ and P. D. Eastman’s Are You My Mother? I went about the world interviewing any expert in systems thinking who would speak to me asking a simple question, “What is systems thinking?”

Their answers were both enlightening but ultimately disappointing. As Henry David Thoreau eluded to, when it came to systems thinking, I wanted to…

… live deep and suck out all the marrow of life, to live so sturdily and Spartan-like as to put to rout all that was not life, to cut a broad swath and shave close, to drive life into a corner, and reduce it to its lowest terms.

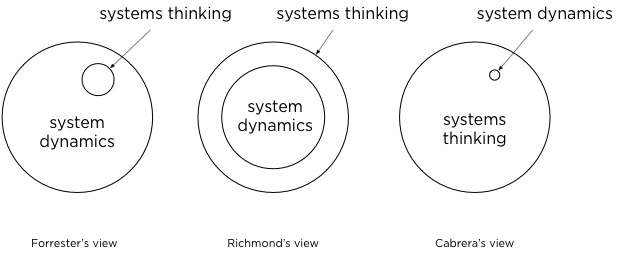

I didn’t want to know what System Dynamics, Soft Systems Methodology, General Systems Theory, or Complexity Theory was per se. I wanted to know what it took for a person to become a systemic thinker. As Basho said, “Do not seek what the great one found, seek what they sought.” Each of those frameworks and models were impressive and even useful for solving certain types of problems. But I sought something deeper. To me systems thinking as a field was a big tent that included many many frameworks and theories, many theorists and thinkers, and many types of practice. I wanted to know what basal, foundational principles — at the time what I called “patterns of thought” — were needed to gain admission to this big tent. I wondered:

What did all of these methods and frameworks have in common?

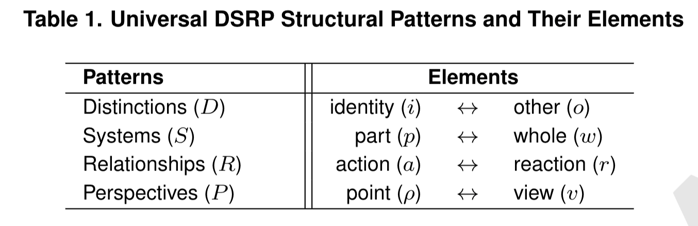

It took many years of cognitive cul de sacs and migraines, and a lot of research to answer this question. I eventually discovered that underlying all forms of systems thinking are four simple patterns of thought that can be combined and recombined in a dizzying number of ways. I named this formulation after the acronym for the four patterns, “DSRP” ( D istinctions, S ystems, R elationships, and P erspectives). But this article isn’t about the discovery of DSRP. This article is about an equally difficult question:

How would one go about doing systems thinking, and over time, learn to be better at it?

The answer to this question would take another ten years of practice and research to uncover. Like the discovery of DSRP, this latter discovery — and the topic of this post — seems drop-dead simple and obvious today, but I assure you that when we were searching for answers it was neither simple nor obvious.

It occurred one day when my colleague, Laura, and I were discussing our NSF grant and our work with doctoral students in getting them to understand the complexities and concepts behind DSRP. Laura — an expert in translational research — said, “why don’t we work with little ones [children] as these same ideas could be taught to them and we could measure results.” My initial reaction to Laura’s suggestion was mixed. On the one hand, successfully teaching systems thinking to the earliest learners was a deeply embedded goal of mine. On the other hand, it didn’t make a lot of sense to me at the time that if we were having difficulty relaying the concepts to Ivy League doctoral students, that the natural next step was to attempt to relay these same ideas to kindergarteners. Of course, Laura’s intuition was right, but it would be another decade before I would see just how right she was and why.

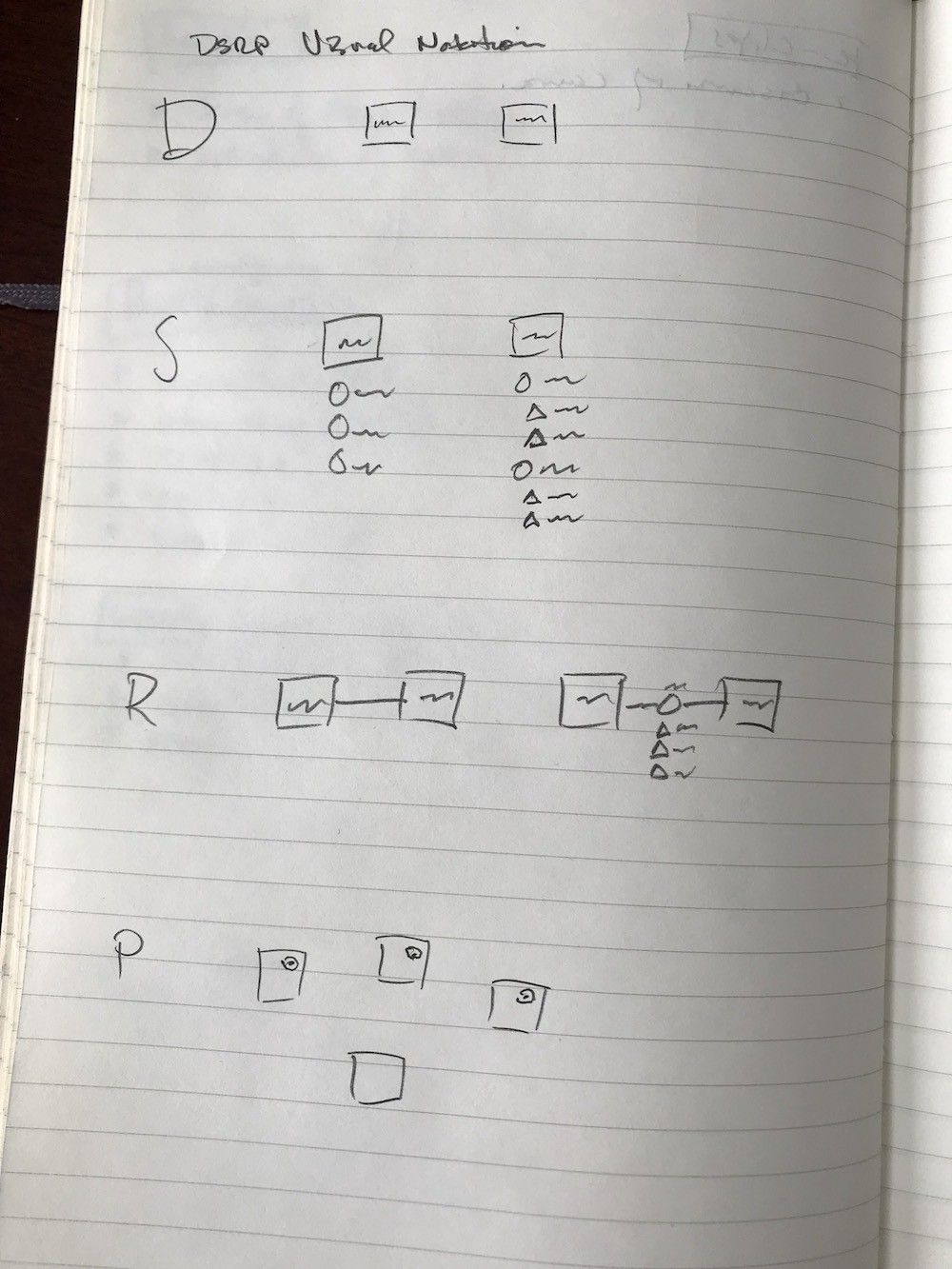

We began teaching the DSRP concepts (aka “systems thinking”) to both teachers and children in grade schools. At first there was a significant learning curve because — like our doctoral students — some teacher’s initial reaction was, “these ideas are very abstract.” It was a long evolutionary process to make the ideas less abstract, more tangible, more tactile, and more visual. There are more neurons connecting our brains to our hands (tactile) and eyes (visual) than to all of the rest of our body combined. This means that humans are inherently visual and tactile thinkers. One day, I scribbled a few drawings in my notebooks — a kind of visual short-hand for DSRP.

We began using this visual notation on blackboards, whiteboards, and large sheets of paper to teach teachers and students to “see and draw their thinking.” These four visual notations could be mixed and matched to form any number of combinations and flexibly used to describe any thought but also to extend or generate new thoughts that might otherwise have gone unthought…

We immediately saw an uptick in understanding and in impact. Each time we visited classroom we would see numerous “DSRP Diagrams” on the walls. Even more exciting was seeing walls lined with diagrams made by kids of the thought processes they used to better understand any topic in any grade.

Teachers and students from across K-12 shared their DSRP Diagrams with us and with each other, often by taking photos and sending them via email or text message. For nearly five years we watched as the visual language became more sophisticated in describing and prescribing fluid thought. We soon learned that photos were a pain and that it was problematic to erase or redraw maps as thoughts changed. Maps got messy with all the thinking and editing. It dawned on Laura and I that we would need to create visual mapping software to remedy these many problems.

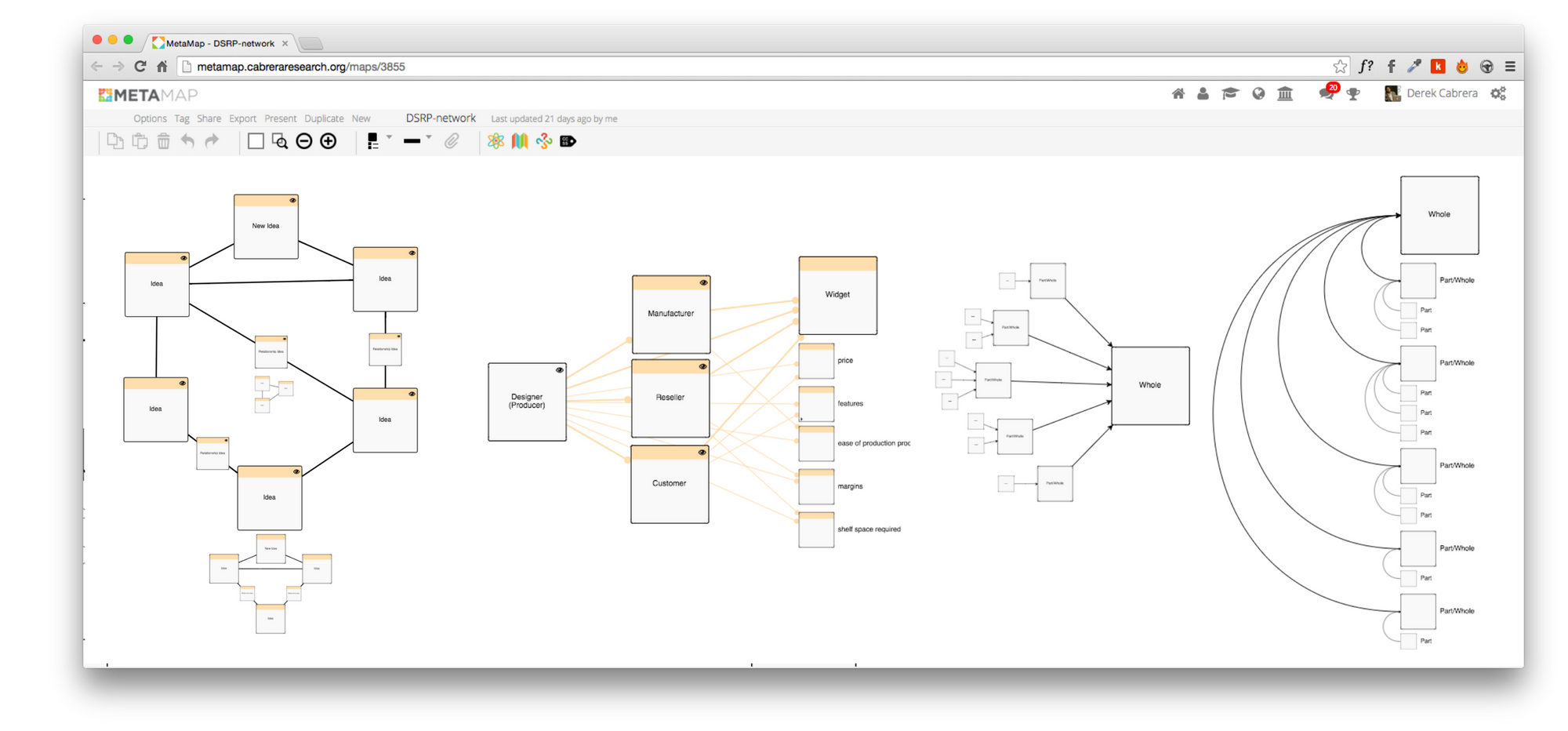

Not being programmers, Laura and I were near clueless as to how to go about building software. We decided to build a very simple software we called “MetaMap” (a portmanteau of metacognitive + map). We developed the software and tested it for another five years. What we saw was that the underlying DSRP architecture was capable of mapping “anything anyone could think” even in a very simply designed software. We were always looking for “edge cases” of complexity to test the architecture, but time and again, where sometimes the software failed us, the architecture did not.

Fast forward a number of years and MetaMap has become an emerging powerhouse we now call “Plectica” (the name comes from plectics , the Indo-Latin root that underlies both the words simple and complex). What I am most excited (and proud) about Plectica is that we can now answer the second question: How would one go about doing systems thinking and learn to do it better and better? The answer is: use Plectica.

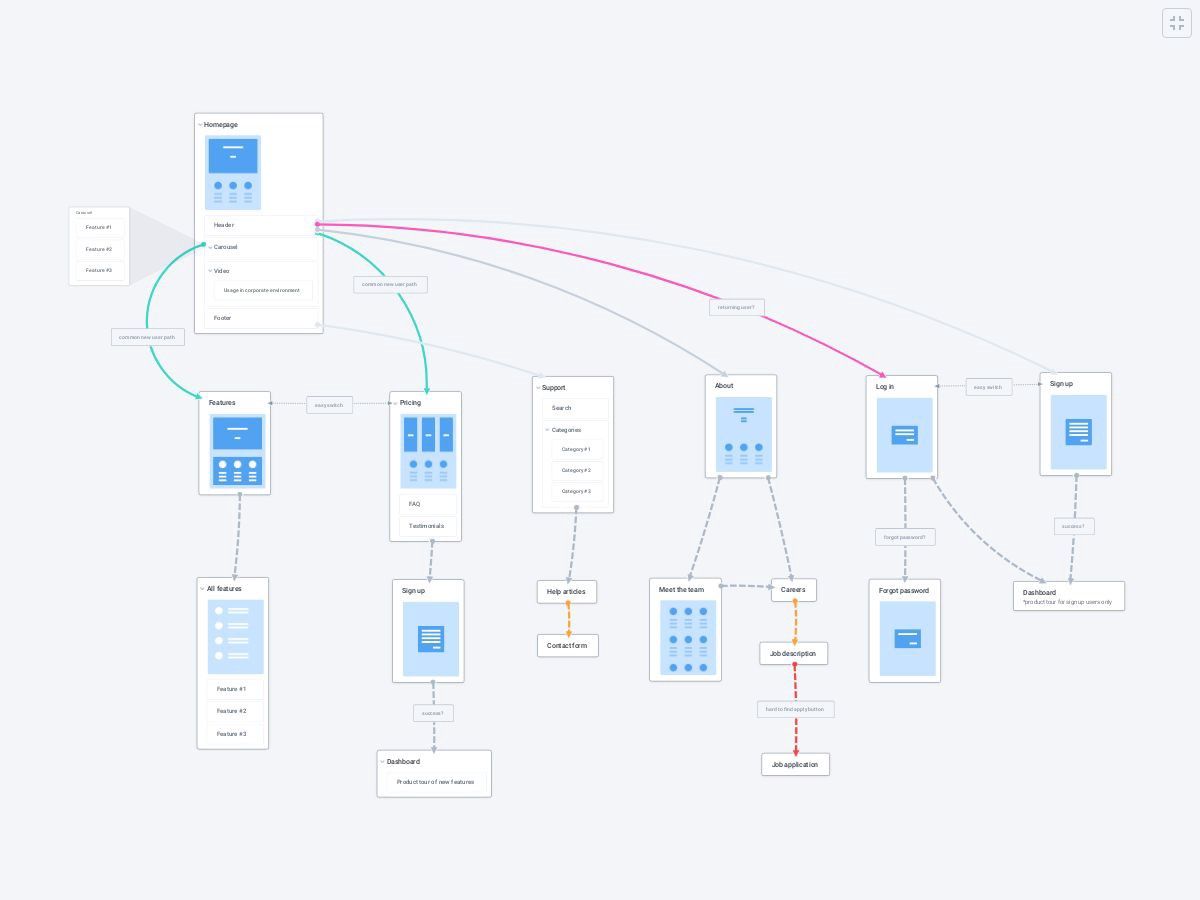

Plectica will not only allow you to record and describe your thoughts, its DSRP cognitive architecture is also prescriptive, so you will have thoughts you might not otherwise have had. Plectica is systems thinking software designed for systems thinkers, by systems thinkers. Take a look at some examples of the kinds of maps Plectica can create using just four basic patterns of thought. Plectica has the same DNA as MetaMap but it truly expands what is possible. It allows you to to do what we call the “4 Cs:” C larify, C apture, C ollaborate, and C ommunicate any idea you can think of about anything you want to think about. One of the most exciting aspects is the ability to collaborate with others in real-time on systems mapping. No more texts with static, low resolution photographs of whiteboards!

For me personally, Plectica completes the shift of myself from a systems thinking novice to a systems thinking expert today. As a novice, when I heard about the potential of systems thinking I was excited, but as I drilled into it I longed for some applied tool that I could use to get better. I was enamored by the powerful concepts, but I wanted more. I wanted to do systems thinking. All I wanted was for someone to say, “do this over and over again and you will get better at doing systems thinking.” But I never found it. (And, it shouldn’t take a person over twenty years to get good at doing systems thinking!)

In a way, what this visual language of systems thinking does is — distinguish conceptual systems thinking from the applied systems thinking I call systems mapping . What I love about systems mapping is that a novice to systems thinking can come to it with absolutely no knowledge of systems thinking. No knowledge of DSRP. And by moving object-oriented ideas around a canvas to visually map one’s ideas, one can begin the journey toward becoming a systems thinker. As you use the canvas, you learn more about the structure of systemic thought without even knowing you are learning it. You need not engage with any confusing jargon, rhetoric, or terminology. You just descriptively and prescriptively map your thoughts using the inherent and natural architecture of the Plectica canvas.

What I love about Plectica systems mapping is that it can be used for the simplest of tasks (A shopping list or rethinking how meetings are run) but it doesn’t shy away from the most complex cognitive maps a person can dream of. It makes systems thinking something I can do everyday in every way. And, it democratizes systems thinking, because it is entirely accessible to any person regardless of their background knowledge.

The promise of systems thinking for society writ large is massive. The potential of systems thinking for understanding complex and everyday systems is high. Thus, the potential for solving wicked and everyday problems with systems thinking is equally high. But without tools, systems thinking is like a carpenter with little more than his hands to work with. Plectica provides the tool set. I am excited to see what all the carpenters in the world can do with it.

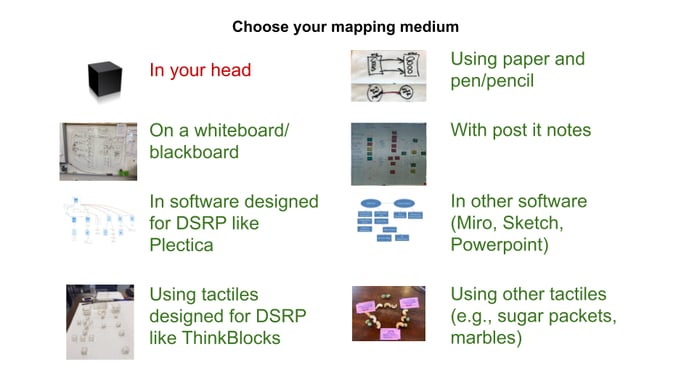

Now, I know that I just told you that the answer to the question: How would one go about doing systems thinking and learn to do it better and better? is use Plectica. And, there is a great deal of truth to that. Using Plectica software makes it easy to create things and move things around in a visual language of systems thinking. But the deeper answer to that question requires that we not mistake the medium for the mapping. In truth, there are any number of media we can choose when we are mapping. Being able to move fluidly from one to the other i the true sign of an expert systems thinker.

Distinguish the Medium you are using from the Mapping you are doing

Distinguish the Medium you are using from the Mapping you are doing

The best way to become an expert systems thinker and systems mapper is to focus on the 4 underlying Patterns (DSRP) and their two co-implying elements. This will provide you with a fluid ability to use any medium in any context.

Want to learn more? Get the book or learn more about Training and Certification.

Want to learn more? Get the book or learn more about Training and Certification.

.png?width=150&height=150&name=CRL%20GOAT%20Logo%20(4).png)