The Four Flawed Mental Models Of Organizations: Mental Model #1

Derek & Laura Cabrera

·

4 minute read

Derek & Laura Cabrera

·

4 minute read

This post is an excerpt from Flock Not Clock: Chapter 1.

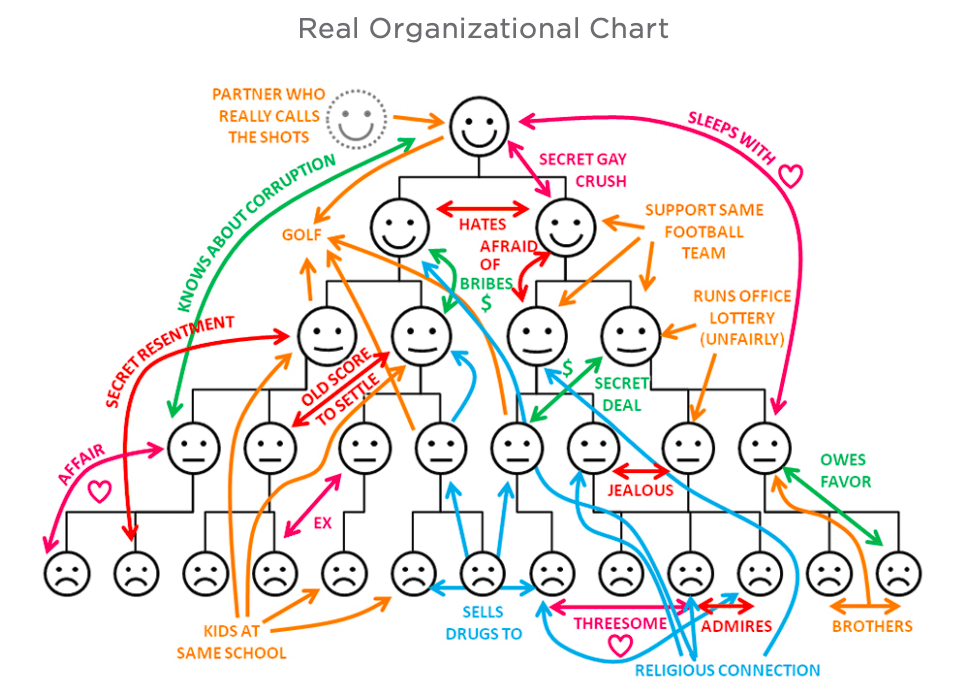

Our more complex problems come about when how we think our organization works is out of alignment with how it actually works.

The traditional model of organizations is based on several significant mental model errors. Why are we committed to a model that is so often wrong? The starting point for these thinking errors is the overarching metaphor that we use to think about organizations: a clock or a machine that can be engineered, tweaked, retooled, recast, or fully understood. Organizations are more organic, adaptive, human, complex, and volatile than clocks. They are not like clocks. The traditional model of organizations can be summarized as plan, command, control, and utilize resources. To say there is room for improvement here is a wild understatement.

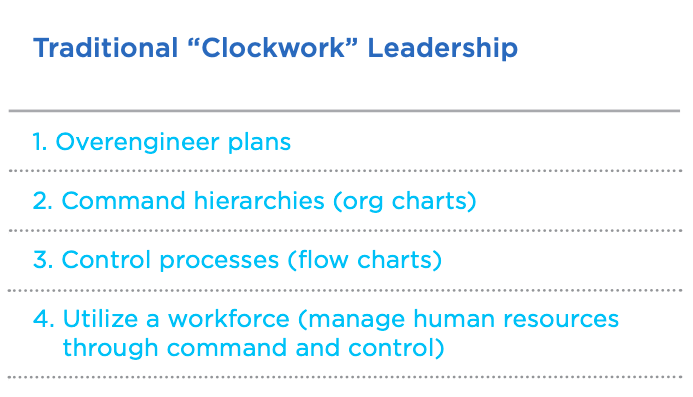

Table 1.2: Traditional model of organization

Table 1.2: Traditional model of organization

Flawed Mental Model #1: Plan

First, we need a plan. We used to think we could plan 10 years in advance. Then someone figured out that was crazy talk and the five-year strategic plan was born. Ironically, it took more than five years to realize that five years is also a really long time. Compounding this problem is the fact that the speed of change in markets, society, culture, and technology is accelerating, making each year an even longer time, relatively speaking. So we moved to the two-year plan. The two-year plan was much better because it was nearly 60% more accurate! Of course, we soon realized this, too, was a really long time in business years, which are roughly akin to dog years. So we’ve settled on “We just need a business plan because we can’t get money without one.” The basic idea is that there is something magical about a plan. You need to have a plan… or do you?

We are not against planning. We are against hubris. Planning, as it is currently practiced, looks a lot like hubris. Hubris that you can predict the future and account for all the variables and all the actors in the complex system that makes up your business, your market, your industry, or the global economy. The truth is there’s a lot of luck and randomness in complex systems. And there’s a lot of complexity and interactions that cannot be known. Unless you have a crystal ball (or Google's server data), you’re better off focusing on simple rules rather than trying to predict the future.

Not all planning is bad. But we must put planning in real VUCA world contexts to understand their utility. General and later president, Dwight D. Eisenhower, said, “In preparing for battle I have always found that plans are useless, but planning is indispensable.” To plan is to think through all the possible alternatives and weigh the pros and cons of each. But we cannot get locked into our plans despite the changing environment, or even confirm their assumptions (confirmation bias) because we are so invested in seeing the outcomes the way we’d planned them. We should keep in mind the saying popularized by John Lennon: “Life is what happens when you are making other plans.” So, first and foremost, we must remember that plans are merely mental models about the future and how it will play out, and we must ensure that we update those plans constantly as we get new feedback, information, or signals from the real world.

The second thing to remember about planning is that if planning is a line, made up of some number of points, there are two points on that line that are the most important to clarify with your team: Be brutally honest about where you are—your starting point—and be crystal clear about where you want to go—your ending point or goal. As a long-time mountain guide, I watched confirmation bias and reality bias in action more times than I wish to remember when I watched groups reading maps, orienting themselves to the real world mountain environment, wishing they were standing somewhere they were not and making the terrain fit their mental model of where they thought they were. They didn’t trust the terrain, they didn’t trust the contour lines of their map, and they didn’t trust their compass. They trusted their deep desire not to be in a place that meant they had a long day, a steep climb, or a difficult challenge ahead. Being brutally honest about where you are—when your product isn’t up to snuff, when your mental model is flawed, when your customers are disappointed, when you are the problem—is the first and most important point on that planning line. The second is the end point. The vision. Ensuring that everyone has the same goal ensures that at each point each person is attempting to maximize the chances of reaching that goal. We will talk a lot about this ending point in Chapter 2 (Vision).

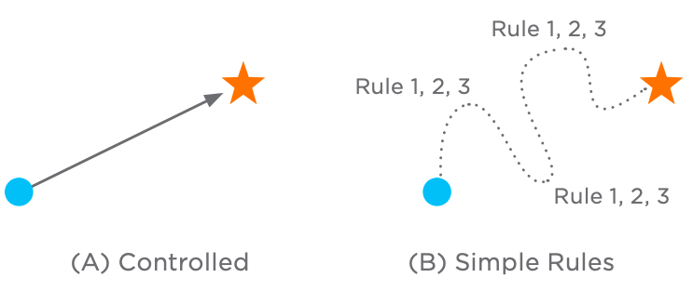

But if we want to understand how a bunch of people are somehow going to start acting like a superorganism to get things done in an adaptive way, then we need to revisit simple rules and complexity. The best way to get a group of people to work together to bring out the power of their collective dynamics is to give them a simple set of rules and a shared vision (a North Star, so to speak). Think of it this way: if you want a group of people to end up in a particular location, you have to tell them where it is, motivate them intrinsically and extrinsically to get there, and tell them the rules they should follow on the journey. What you don’t want to do is micromanage the journey, because things on the ground might be difficult and complex and require adaptivity and grit. What you want to say is: here’s the destination in all its glory and here are rules for getting there. So let’s say you know where you are and where you want to go (vision). We’ve been taught since third grade that the shortest path between two points is a straight line. And since third grade we’ve been imposing this limited truism like a bully on every process we meet. Although it’s mathematically true that the shortest path between two points is a straight line, it’s not necessarily true in practice when we have countervailing forces and unknown or unexpected variables. Let’s say, for example, that in between point A and point B there is a swamp. Add alligators and botulism to the swamp and suddenly the most costly, most time-consuming path is the straight line. Yet this straight line or linear mental model is more popular than you might think. We use it whenever we think that the path between A and B is completely definable even though it is a path in the future through a complex and ever-changing landscape.

Figure 1.7: Contrasting mental models of process

Figure 1.7: Contrasting mental models of process

Figure 1.7 shows two different mental models. In (A) we see where we are, where we want to go, and how we will get there. This represents linear thinking. In (B) we see where we are and where we want to go, but our journey is a bit different. Instead of a simplistic and linear projection, we take into account the unknown. This path is nonlinear, projected rather than definitive, and adaptive, using simple rules to guide what might be a complex trip.

See the next mental model here.

.png?width=150&height=150&name=CRL%20GOAT%20Logo%20(4).png)