All Organizations Are Complex Adaptive Systems

Derek & Laura Cabrera

·

3 minute read

Derek & Laura Cabrera

·

3 minute read

You don’t get to choose whether your organization is a complex adaptive system. All organizations are complex adaptive systems because they are made up of individuals (agents) adapting to their environment. The behavior of an organization—an emergent property of the many agents and their interactions with one another and their environment—is not easily predicted by the behavior of the organizational members alone. As a leader, your challenge is to embrace this reality and leverage it to your advantage.

Excerpt from the book: Flock Not Clock, Chapter 1

As complex adaptive systems, all organizations are learning organizations: they test mental models (or schema) of how things work against feedback from the real world. However, in the same way that a child can learn and build maladaptive mental models based on their experience, organizational learning can reinforce maladaptive collective behaviors and cultures. For example:

- A punitive CEO might foster a culture of silence, in which people are afraid to raise concerns or take risks.

- A company that rewards employees for getting along with others and avoiding conflict may never challenge the status quo, thus decreasing creativity and innovation.

- A company built on the successes of a few renegade employees may have difficulty achieving scale.

The ability to adapt [FN1] is critical for navigating a constantly evolving environment, and cultural norms play an outsized role in determining adaptability. For example, we have worked with a large Chinese conglomerate that was originally a regional airline, an extremely technical and logistics-heavy business. Growing into a multinational company meant adding new and less technical products and services. Their highly structured origin model, which focused on engineering, had created a culture which was slower to adapt and evolve toward these less technical opportunities: individual employees accustomed to being highly directed by leaders and required detailed specifications in order to move forward on a project. The CEO wanted them (and needed them) to have more freedom to operate and adapt in creative ways which would create opportunities for new business segments and new markets.

The ability to adapt is critical for navigating a constantly evolving environment, and cultural norms play an outsized role in determining adaptability. For example, in our work with General Electric (GE), we see a company in the midst of a major adaptation. GE was the industrial leader. But when manufacturing went agile and new technology made it possible to 3D print even the most sophisticated parts, the environment shifted relatively quickly from industrial to digital industrial. GE’s leadership saw the future and recognized that in order to continue their leadership into that future, they would need to change their existing industrial mental models to digital industrial mental models.

The challenge is to create an organization that learns how to survive and thrive through adaptation. We need organizational learning that is focused on improving our capacity to achieve our organizational goals. We need systems to ensure that the most productive individual learning is disseminated throughout the organization.

From our understanding of complex adaptive systems, we know that if we want to influence the emergent properties of a system, we need to tweak the agents and/or the simple rules. To create system-level behavior, we must focus on the underlying rules that produce it. Therefore, a leader’s power lies principally in selecting agents and deciding, implementing, and enculturating simple rules for the organization.

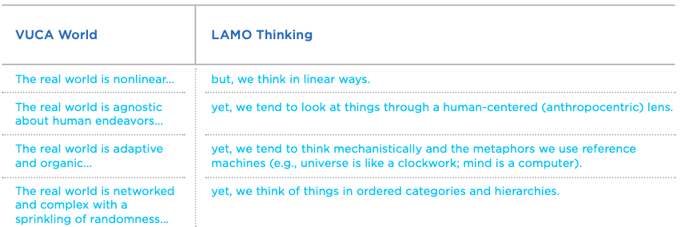

We want our mental models to align with how the real world actually is. We live a world characterized by volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (VUCA). And while the real world is VUCA, we tend to think about the world in linear, anthropocentric, mechanistic, ordered (LAMO) ways. This mismatch has several implications, as you can see in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1: VUCA world, LAMO thinking

Table 1.1: VUCA world, LAMO thinking

In short, our thinking is biased in ways that don’t align with objective reality. We project this bias onto the world and often miss the critically important feedback the world is giving us—feedback from a multitude of sources. And feedback is critical for fueling our learning, development, and adaptation, as individuals and as organizations. So what is the source of our bias? How do we come to understand it, and how do we change it? In large part, it comes down to mental models.

[FN1] A lot of folks think of adaptation as inherently positive. The problem is, whether something is maladaptive (mal = bad) or bonadaptive (bon = good) is often something that is determined somewhat subjectively and in retrospect. Adaptivity is therefore better thought of as being +/- neutral at the center of a continuum

.png?width=150&height=150&name=CRL%20GOAT%20Logo%20(4).png)