Could Cognitive Jigs Be the Missing Link to Better Problem Solving? An Interview With Dr. Derek Cabrera

Staff

·

9 minute read

Staff

·

9 minute read

To read more about jigs, check out the help article on jigs and also check out the cognitive jigs tag...

Staff: You've been talking a lot about Jigs lately, what’s that all about?

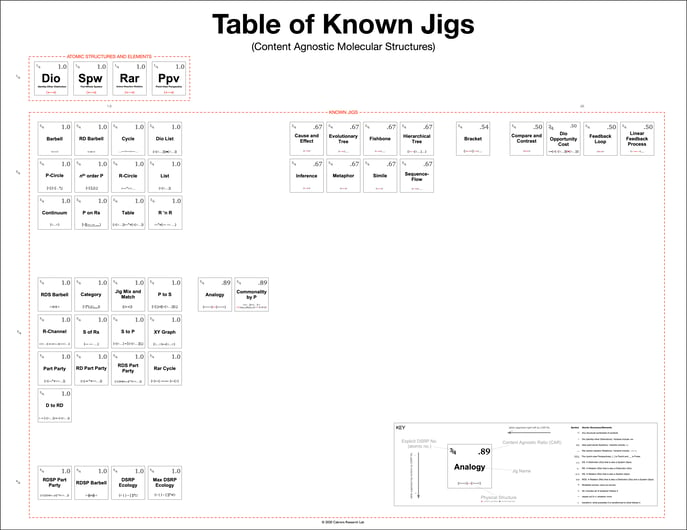

Dr. Cabrera: Yes. Jigs are very exciting and the new work we've been doing on them is even more so. Without knowing them by name, humans have used cognitive jigs for millennia in the form of analogies, metaphors, similes, lists, tables, graphs, etc. They are, in fact, some of the most powerful tools in our cognitive arsenal in solving wicked and everyday problems and just generally deepening our understanding about any topic in any domain.

Staff: What makes jigs, and the new work in them, exciting?

Dr. Cabrera: Part of it is the immense potential that new work in jigs has and the other part is a re-realization of their importance and their potential. We’ve always known they were important and we’ve always known that folks who learn systems thinking by learning jigs find it helpful because they report it to us a lot. But, we are now on a cusp of clarity about what jigs are, why they are so special, and what they are capable of. Most importantly, there are 44 known jigs but potentially dozens or hundreds more yet to be discovered. I think the idea that we might discover new jigs, as yet unknown, but potentially lurking and in use all around us, is exciting!

Staff: You’ve written about jigs before and explained a lot about the basics, so I’d like to focus more on where you see “jig science” going? What do you see on the horizon?

Staff: You’ve written about jigs before and explained a lot about the basics, so I’d like to focus more on where you see “jig science” going? What do you see on the horizon?

Dr. Cabrera: Jigs are content-free structures underlying our thoughts (cognition). They manifest as molecular structures coming from the atomic structures of DSRP. But they are quite different from frameworks in their structure and their dynamism. They are structurally content-free. But dynamically, they are modular—meaning you can mix and match them to form even more complex cognitive compounds. Because they are content-free, they are very agile, adaptive, fluid, and flexible. As a result of all that they are quite useful. This might sound absolutely bonkers, but I imagine that a future mind, armed with DSRP and a relatively small set of jigs, will be far more capable and effective than that same mind toting around a number of frameworks. Yet, today, we focus almost exclusively on frameworks, especially in advanced and graduate studies.

Staff: This is a hard concept to grasp. Can you give us an example?

Staff: This is a hard concept to grasp. Can you give us an example?

Dr. Cabrera: We have all these amazing drugs. And when you get sick or have a headache, you can take a pill and it makes you better or your headache goes away. Sometimes the drugs work and sometimes they don’t and sometimes they really screw you up. But imagine that we start to develop some drugs that are based on basic structures but that can be completely customized to your DNA. So they work perfectly for you and there are no negative side effects. The promise of that type of solution is, for the healthcare industry, on the near horizon. In some cases, it is already here.

Imagine a similar situation where rather than physical ailments, we have personal, professional and psycho-social maladies—in other words, we have everyday and wicked problems in our lives. Now imagine that we have these various “remedies” for these problems that we’ll call frameworks. We use these frameworks whenever we run into a problem. And there are very specific frameworks for specific problems. The issue is, the problems are too complex and the frameworks don’t always fit. They don’t help solve the problem. That’s because the wicked problem requires a custom, bespoke framework made just for it and all the frameworks available are not made to fit; they’re off-the-shelf versions that most people have to shoehorn the problem into to make it work. In other words, our current reliance on frameworks is a bit like the non-customized medicines of today. There's more potential for something different.

Imagine a similar situation where rather than physical ailments, we have personal, professional and psycho-social maladies—in other words, we have everyday and wicked problems in our lives. Now imagine that we have these various “remedies” for these problems that we’ll call frameworks. We use these frameworks whenever we run into a problem. And there are very specific frameworks for specific problems. The issue is, the problems are too complex and the frameworks don’t always fit. They don’t help solve the problem. That’s because the wicked problem requires a custom, bespoke framework made just for it and all the frameworks available are not made to fit; they’re off-the-shelf versions that most people have to shoehorn the problem into to make it work. In other words, our current reliance on frameworks is a bit like the non-customized medicines of today. There's more potential for something different.

Staff: I wonder if you could give the reader an idea of how cognitive jigs interact with mental models generally. Where do they fit in? How are they related?

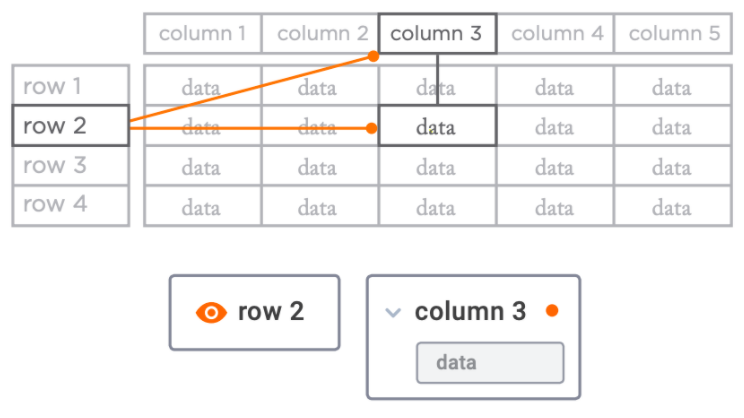

Dr. Cabrera: Mental models are made up of information and structure. We know that they're made up of a DSRP structure and we know that structure can contain information.

Think of it as a bunch of different buckets and tubes and a bunch of different ping pong balls. Depending on the way you organize the buckets and the tubes flowing into each other, flowing out of each other, above each other, below each other, then the ping pong balls will do different things and it'll create a different system with a different meaning. The structure helps make meaning out of the information. This makes mental models; mental models are the same as meaning.

Staff: I see, a jig is a mental model that has very little or no informational content. Can you say more? Is a jig a content agnostic mental model that you can put content into?

Dr. Cabrera: Yes! It's a structural model that could be applied in any domain and therefore any type of information could be put into that model. So in the case of the example, instead of ping pong balls, you could have rabbits or fish or anything.

Staff: I think the use of the term structural model is easier to understand because one can obviously think about an analogy as a structural model that you put words into to create a meaningful concept or thought.

Dr. Cabrera: An analogy is a jig. So humans have been using jigs without knowing that they were called jigs. We've started calling them jigs in the last twenty five years, but we've been using jigs unbeknownst to us for millennia. These jigs include analogies, metaphors, similes, tables, XY graphs, lists, etc.

Your grocery list is a jig. A common structure. But your grocery list could have anything in it. You know, it could be very different week to week. If you're going to Home Depot, it could be very different than if you're going to Wegman's or a different kind of store. But the list, the underlying structure, stays essentially the same. So, it's a go to structure that is super flexible. And of course, it's also modular, you can stick a list inside of a feedback loop, a table, an analogy, etc.

Staff: And the reason they're jigs is that they give people a structure into which they can put content?

Staff: And the reason they're jigs is that they give people a structure into which they can put content?

Dr. Cabrera: Yes. Any content.

Staff: I see. So in a weird way then you could say not only is a jig a structural model, it's a tool.

Dr. Cabrera: It's a very powerful tool. If you want to use the tool metaphor, think of it this way: I might have a tool that's incredibly specific for scraping latex paint off. That's a very specific tool that's only good for one thing, like a stud finder, a tool that helps you find the nail that's in the wall using a magnet so that you can hang a frame. In contrast, a jig is a nonspecific tool that is universalizable because it can receive any content. It’s more like a hammer or a screwdriver - both of which are basic tools that we use for almost everything. Every household has a hammer, screwdrivers, scissors, tape measure. Those are used over and over again. That's what jigs are like.

Staff: What you're saying is that frameworks are useful, but they're useful for very specific purposes, whereas jigs are used for many different things.

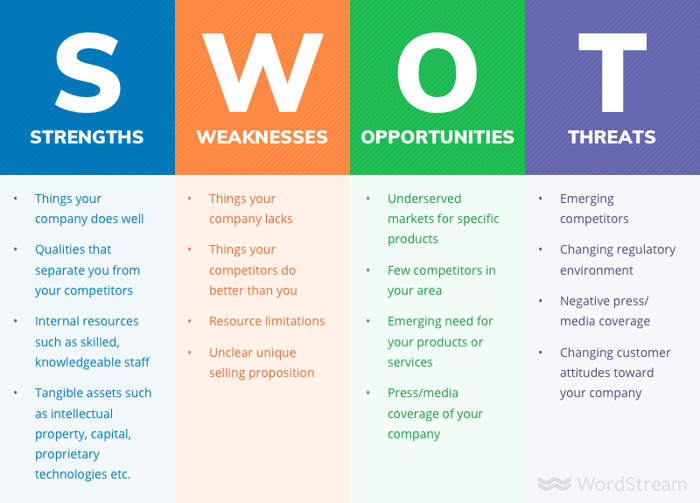

Dr. Cabrera: Yes, frameworks tend to be larger and they're full of content and structure. So a framework is like purchasing a table saw. It's a big thing, it's a big investment, you've got to learn how to use it much like a framework. You've got to understand how to apply that framework. It has all these pieces to it. You've got to set it up. You've got to plug it in. There is a relatively high cost to learning anew framework like System Dynamics, or Soft Systems Methodology, or Design Thinking, or SWOT Analysis. Those are big, cumbersome tools.

Staff: I'm glad you brought that up, because you have referenced this concept of shoehorning.

Dr. Cabrera: Shoehorning relates to that sort of clunky, cumbersome nature of a framework. Shoehorning comes from, metaphorically speaking, when you can't fit your foot into your shoe, you take a leveraging tool to fit your foot into a shoe. Shoehorning effects—when dealing with mental models—happen when we force a square peg into a round hole.

Because you have a framework that you've invested time in learning, you want to use it because you learned it and it's sitting there and you understand it and you were told it was useful. So, when a problem comes along, you'll naturally look for how you can apply your framework to this problem. In that moment, we create another problem/issue, which is that we are shoehorning the problem into the framework. And that's exactly the opposite of what we want to be doing. What we want to be doing is building a bespoke model that fits the problem as closely as possible.

Because you have a framework that you've invested time in learning, you want to use it because you learned it and it's sitting there and you understand it and you were told it was useful. So, when a problem comes along, you'll naturally look for how you can apply your framework to this problem. In that moment, we create another problem/issue, which is that we are shoehorning the problem into the framework. And that's exactly the opposite of what we want to be doing. What we want to be doing is building a bespoke model that fits the problem as closely as possible.

Staff: If you shoehorn a problem into a framework, you might, for example, frame the issue differently? Or you might miss a variable?

Dr. Cabrera: Yes, when we try to shoehorn a problem into a framework, it essentially makes it so we don't see the problem in the way that it actually exists in the system structure. The way it exists in "nature."

The classic example is SWOT analysis. There's Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats. It's a framework. Lots of people learn it in grad school or, you know, business school or wherever. And you see people applying it to all kinds of problems. The question is, are you just taking the problem or system at hand and and shoehorning it into the SWOT analysis framework?

Staff: I see, the framework is biasing the problem in how you see it in the first place. Why is it important for me to start seeing and using jigs to improve thinking?

Staff: I see, the framework is biasing the problem in how you see it in the first place. Why is it important for me to start seeing and using jigs to improve thinking?

Dr. Cabrera: Well, first they're content-free. Second, they're very small, they're lightweight. Each individual jig is a very small structural tool. Whereas frameworks can be quite large. If you look at system dynamics, soft systems methodology, agile or design thinking or any of these frameworks, they're quite large and their bulkiness and content-dependence makes them hard to use.

A jig is content-free. It's stripped of content and it's very small. And as a result, you can mix and match jigs to create larger structures that mimic the problem structure. So you can think of Jigs like Lego pieces that you can put together to create any structure that you want to use to better understand a problem.

Staff: When you say the structure fits the problem, why is that an important concept?

Dr. Cabrera: Well, fit is everything because you can't understand the system nor solve the problem that is coming from a system without getting your mental model to be structured as closely as possibleto the way that the system is actually structured . Whether you're dealing with how to get a student to behave in the classroom or whether you're dealing with how to get the United States or any other entire country through the COVID crisis. If you don't understand the structure of that problem, the structure of that disease, how it spreads, and the various ways that that disease not only affects an individual person, but how individual people affect each other based on how it spreads socially and how to prevent that. In other words, if your mental model is out of touch with the reality of that system, whatever solutions you come up with, will be out of touch. And the same thing goes for student behavior.

Staff: Okay. I understand that the fit is what matters and that jigs are better designed for that because they're a structural tool or structural model.

Dr. Cabrera: They are better at bringing the structure of that mental model about a problem, issue or situation to the surface. So jigs, as a tool, create better alignment with the problem as it sits, so the solution will also be improved.

Staff: How exciting is the future of jigs?

Dr. Cabrera: It's pretty exciting because what we've done is identified this structure that has existed for, like I said, millennia. And humans have been using these things forever. And the things that we are readily aware of, like analogies, similes, metaphors, tables, lists, XY graphs are all incredibly useful and pervasive in our lives. So we know that they are very useful. We know that they are relevant and important. But what's really exciting is that there could be so many more of them.

Staff: I think that's the part that is hard to grasp. You're saying that there's this whole realm of undiscovered little simple tools we can use to understand how we're thinking about things?

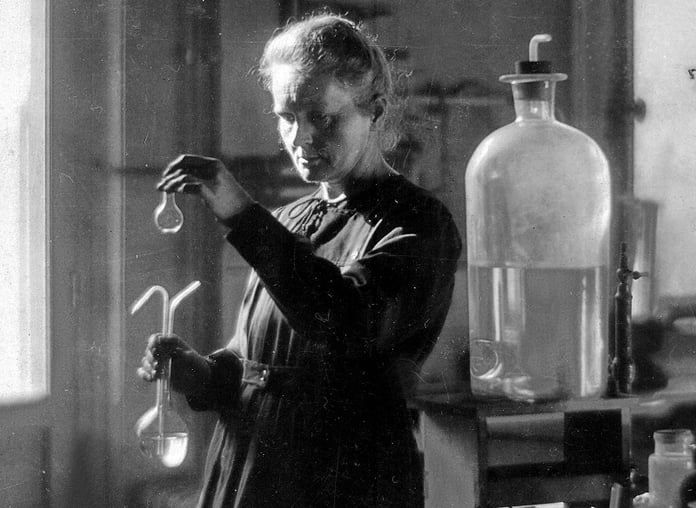

Dr. Cabrera: If you were a historian of science, you could look at this moment in cognitive science and in personal development and human development, and you would see it almost like a time when Marie Curie was alive. And, the periodic table of elements was relatively new. Yet there was much to continue to be discovered there. She was able to discover polonium and radium, two elements that no one had ever discovered before, for which she was awarded the Nobel Prize twice. She added two important new elements to the periodic table of elements. There’s a similarity to cognitive jigs, because in the beginning, it was quite easy to find elements because we were already using them. And we found forty four of them. What I get excited about is the continued search for more of them, because there could be, I don't know, dozens more, there could be hundreds more. Ironically, there are jigs that are universal to all things. And then there could be jigs that are universal to certain disciplines. But, it opens up a world where we can begin to look for them. It's a world where things can be discovered. I think they very much have the potential to give us great clarity about what it means to be truly a great problem solver, a great thinker, and what it means to do systems thinking (in terms of Kahneman’s work on type 2 thinking, rather than on type 1 thinking).

I think jigs extend our abilities as humans. And I'm excited about finding more of them. When I was a climber, everything was about the first ascent, much like Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay got the first ascent of Mount Everest, the first ascent of any mountain is an amazing thing and the same is true in science. It's like when Madam Curie found polonium and radium it was a big deal. It's exciting that people could discover these new jigs because they're not as easy to find as you would think. The discovery of each new one, much like a new element, gets harder and harder.

I think jigs extend our abilities as humans. And I'm excited about finding more of them. When I was a climber, everything was about the first ascent, much like Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay got the first ascent of Mount Everest, the first ascent of any mountain is an amazing thing and the same is true in science. It's like when Madam Curie found polonium and radium it was a big deal. It's exciting that people could discover these new jigs because they're not as easy to find as you would think. The discovery of each new one, much like a new element, gets harder and harder.

Staff: So when something like radium is discovered, you gain insight into a bunch of other things.

Dr. Cabrera: Yes, exactly. Each jig is analogous to that.

Staff: Ironically, using an analogy to describe it - the discovery of each jig is a window into a whole bunch of other knowledge.

Dr. Cabrera: That's absolutely right.

Staff: Thank you for your time today.

Want to learn more about jigs? Read about them in Systems Thinking Made Simple.

Or for more advanced treatment read: Cabrera, D., and Cabrera, L. (2020). Cognitive Jigs: Content-Free, Modular, Molecular, Structures for Understanding and Problem Solving. Journal of Applied Systems Thinking. (20) 10

.png?width=150&height=150&name=CRL%20GOAT%20Logo%20(4).png)