Slider: K/DK: An Interview With Dr. Derek Cabrera.

Staff

·

7 minute read

Staff

·

7 minute read

Learn more about the definition of a slider, or read our other sliders...

Staff: This slider is called "K & DK." Can you tell me what K and DK stand for?

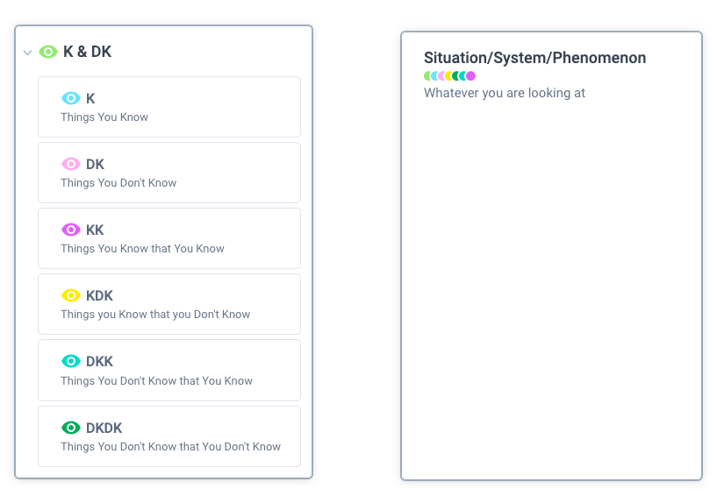

Dr. Derek Cabrera: K stands for “things you know” and DK stands for “things you don't know. There are combinations of K and DK, as well. There's things you know that you know (KK). There are things you know that you don't know (KDK). Then there's things that you don't know that you know (DKK). Lastly there's things you don’t know that you don’t know (DKDK).

Staff: What is the purpose or the benefit of this slider?

Dr. Derek Cabrera: Whenever you're analyzing any system in order to try to understand it, it's important to take perspective. So, you can build a part-whole system made up of all these combinations of K and DK. Then, you use that system as a perspective on whatever system or topic you're analyzing.

Staff note: (See Figure 1 for map of K/DK Slider)

Figure 1: DSRP Structure of the K & DK Slider.

Figure 1: DSRP Structure of the K & DK Slider.

You can say to yourself, "let's look at the system from the perspective of what we know. Or, let's look at it from the perspective of what we don't know. Let's look at it from the perspective of what we don't know that we don't know."

That causes you to think more broadly rather than approaching it with just a single perspective (usually what you know). It's a very basic and simple slider, but it's quite effective if you use it.

Staff: Fascinating. So you use the K/DK System with all of its combinations as parts of the system as multiple possible perspectives on whatever you are thinking about?

Dr. Derek Cabrera: Exactly! Think of K and DK as a whole that can have parts in it, and the parts are K, DK, KK, KDK, DKK, and DKDK. Each of those parts can then become a perspective on whatever system that you're looking at. So, you could go through each perspective (or the salient ones you want to use) with your team...

Staff: When I initially looked at this slider, it appeared redundant to me. For example, K and KK, can you explain to me the distinction between those or some of the other parts that maybe seem a little repetitive?

Dr. Derek Cabrera: The classic example is, if you take an expert, let's say a professional baseball player, and they know how to bat really well like Babe Ruth or Willie Mays or someone more contemporary, Miguel Cabrera. These are some of the best batters in the history of baseball. They know (K) how to bat. But, imagine that they cannot teach someone else how to bat. They don't know what they know. They are terrible teachers. They know how to bat. They bat every day in the professional league. But they couldn't break down what it is that they're doing. They don't know what they know (DKK).

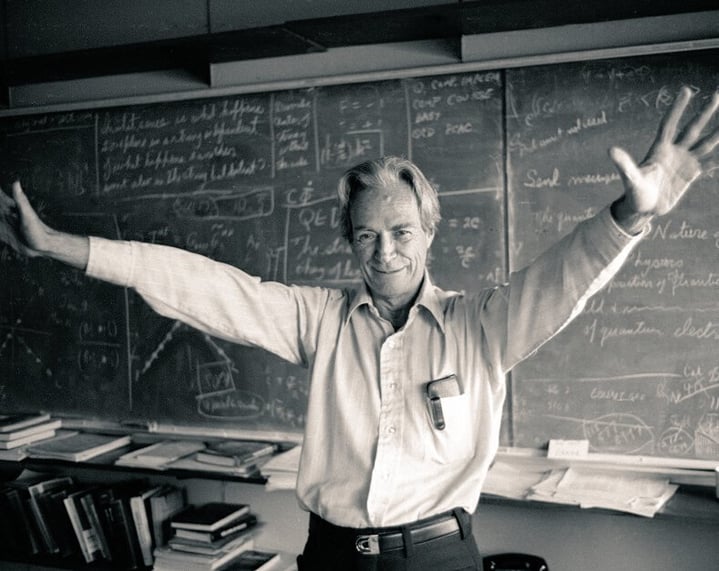

The opposite of this is an expert that is also able to teach others what they know effectively—they know what they know (KK). Sometimes it's great to learn physics from some of the top minds in physics and sometimes it's horrible. The difference is the difference between K and KK. Richard Feynman for example, was not only an amazing and knowledgeable physicist. He also knew what he knew (KK) and so he was also an amazing teacher of physics.

The opposite of this is an expert that is also able to teach others what they know effectively—they know what they know (KK). Sometimes it's great to learn physics from some of the top minds in physics and sometimes it's horrible. The difference is the difference between K and KK. Richard Feynman for example, was not only an amazing and knowledgeable physicist. He also knew what he knew (KK) and so he was also an amazing teacher of physics.

Experts in specific areas often have tremendous expertise. They don't always know how that expertise is structured cognitively so they're not always able to share it with learners.

If I know that I don't know something, take for example the fact that I don't know the extent to which COVID-19 has long term effects on the body. I'm very aware that we all don't know that. That's a KDK. There's probably also DKDK cases out there that I haven't even considered that are just as critically important. So there might be some KDKs and there might be some DKDKs.

Staff: How are you supposed to use the DKDK as a perspective? It seems pretty tricky.

Dr. Derek Cabrera: Yeah, it is very tricky, but the slider is asking you to explore the system in completely different spaces. There's an old saying which is "hindsight is 20/20." When you are looking back, you can see all the places or things that you were blind to.

A lot of people that are trying to solve really difficult problems use that understanding of hindsight being 20/20, but they use it in a prospective way rather than in a retrospective way. They ask themselves, "what are the kinds of things that when we look back on this 20 years from now, we will say ‘how could we possibly have missed that!?’" That's how to use DKDK as a perspective on a system or problem.

We're talking most of the time about very serious things when we do this level of analysis. We're talking about fighting a war in Afghanistan, where people are going to lose their lives. In that case, it doesn't hurt to think about what you don't know that you don't know. These are serious things with potentially dire unintended consequences.

I'm not saying you should do this thorough of an analysis when you're going shopping at the grocery store. But if you're planning something as serious as hurricane relief or a foreign war or trying to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic where people can die or be injured, then these are appropriate perspectives to take. If you're in charge, you should tell your team to “go to another room and think through the DKDK”—what you don't know that you don't know. Find every unintended consequence that you can. If you can catch them before they happen, lives could be saved. There’s great value to going into such an in-depth analysis when the stakes are high.

Staff: It does seem that this slider would be useful in figuring out the COVID -19 pandemic, right?

Dr. Derek Cabrera: Absolutely. Imagine for example if the United States’ plan and response to the COVID-19 pandemic was based on scientists and policy makers actually walking through this slider and planning and setting policy based on what we know, what we don’t know, and what we don’t know we don’t know. I’ll give you just one example, we don’t know (DK) whether this is a one-and-done virus or if it is a lifelong, debilitating disease. We act and speak as if it is one-and-done (or maybe we can get it twice) but the mental model is that you have it and then you are done with it. But what if that’s not true? We are hearing more and more reports of so-called “long haulers.” Justifiably, there has been a lot of focus on death rate but what about the 7.5 million people who may or may not be irreparably harmed for life? What if there is more to this virus than we currently know? There surely is… and we may want to create some contingency plans for those cases.

Staff: Do you think there's anything else that we're missing in terms of understanding this slider?

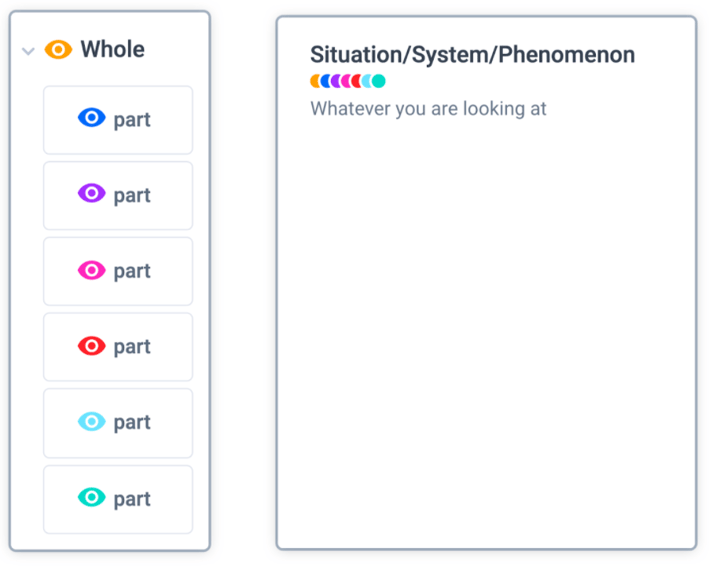

Dr. Derek Cabrera: Yes. I think it is interesting that this particular slider is based on a jig. This fact gives you a neat insight of how sliders are content specific and jigs are content agnostic. The K/DK slider is based on the “S to P jig,” where you take a system and convert it into a perspective, which makes a perspectival system. Next, you analyze another system using the perspectival system you just created. So, structurally, this slider is just an S-to-P jig with specific K/DK content added to it.

Figure 2: The K/DK Slider uses the basic structure of the S-to-P Jig.

So, the K/DK Slider uses the basic structure of the S-to-P Jig. To me, that's very interesting because it gives you a sense of how powerful jigs are. Jigs allow you to be incredibly adaptive and create something like this slider. If you change it and make it something completely different, then you end up with an entirely different slider that's based on the same jig.

Staff: Can you talk a little bit more about the DSRP structure of the K/DK slider?

Dr. Derek Cabrera: Of course. I think it's interesting to note that the whole of this perspectival system is the integration of all six parts (K, DK, KK, KDK, DKK, DKDK) including the relationships between and among them.

If you were wearing a pair of sunglasses and you had six colors that you could see. Putting on the sunglasses would represent the perspective of the whole. This whole would be the combination of all 6 colors and how they interact with one another. If you took the perspective of just one part, let's say blue, then everything you saw would have a blue tint. That is very different from taking the perspective of the whole.

Staff: From a pragmatic view, what does taking all six of these perspectives at the same time look like?

Dr. Derek Cabrera: In practice, you would take one perspective at a time. Depending on the system you are looking at, you might not use all six of them for your analysis. The thing about perspective taking is that the value you get from it varies. Perspectives are formed from the interaction between a point and a view. Sometimes we take perspective because there is value in the point, for example a new stakeholder. Sometimes we take perspective because there is value in the view. So, sometimes, we can use the point to generate a view and then dispose of the point. Once we've gotten the view from that point, the point is no longer important and we can just keep the view. So in a case like this, where you have six abstract concepts of knowing (K) and not knowing (DK), what's important is the generativity of the points to get us some new views. So once you created all those views, you can note down the value of that view, and then you could actually just ignore the points.

In other situations, there is inherent value in bringing in the points and keeping them, like a new stakeholder, your customer, children, etc. Not only are they generating views that are important, but they also existentially are important. Sometimes we take perspectives where the point and the view are both important and sometimes we take perspectives solely to generate the views and then the points are no longer important.

This is a case where the points really aren't that important. They're just generative. In this particular slider, we're working with an external perspectival system that we utilize to get the views.

Staff: It's interesting that through sliders you can hit on or explore different aspects of DSRP that one wouldn't normally get to deeply engage with.

Dr. Derek Cabrera: Yes, sliders are very useful to improve or understand different aspects of our lives.

Staff: How does knowing what you do and don't know impact metacognition?

Dr. Derek Cabrera: Fundamentally knowing about your knowing or knowing about your not knowing (which is essentially the same thing) is a metacognitive act. So it relates to metacognition in that it is metacognition.

An example is that we know from research that when learners of all ages are learning something new to them, being aware of what they know and what they don't know about that topic is hugely important in their ability to learn that content. That is a form of metacognition that helps with learning. This whole slider is fundamentally about awareness of where you're at and it encourages you to search for that awareness.

It is a function of cognition to ask these kinds of questions. What do you know? What do you not know? What's missing from my knowledge? What do I take for granted that I know? What's something that I can't even conceive of that could end up being a problem? Once you are aware of the difference between knowing and not knowing, you can utilize these perspectives to deepen any analysis you are working on. Answering these questions could mitigate unintended consequences and, in some cases, could save lives.

This map shown here is the map of the K/DK slider. It shows the 6 parts (K, DK, KK, DKK, KDK, and DKDK.) The colored dots represent a perspective being taken on the Situation/System/Phenomenon. Interact with this map here.

Want to learn more about DSRP Systems Thinking? Read Systems Thinking Made Simple

.png?width=150&height=150&name=CRL%20GOAT%20Logo%20(4).png)